Knowing is Not Naming by Xiaowei Wang

|

We never spoke about the end of empires, but when it happened, we had not seen each other for years. Somehow it escaped our taxonomy of the world, in between the causally symmetric balances and the notes you kept in the cabinet of a northeast institution, in a town with any latitude and longitude. Like our speech to each other, you defied my intuition, kept order and categories until rationale was exhausted. It happened first on your end of the world, when you gave a night’s walk and noticed the trees full of luminaries. You said to me over the phone how it began on Mott St., an intersection with waning gingkos and brick clad buildings. You thought they were off season holiday lights; decorations for no one’s party. You knew no one better to call, so it was the first time I heard your voice in years. I was alone in an apartment without furniture, body pressed against the floor, monitoring tiny earthquakes against the house’s wood frame as you hurriedly conspired with me about the emergence of these little creatures: Lux meridiani. The aftershock of your voice arrived when I could count time in non-linear cycles again. Measurements and miles, the ratio of one encoded word to another were forgotten. I built systems of knowledge with others, in gardens and warehouses, gallery walls and sheets. The small radio you gifted me playing Brigitte Fontaine no longer held sound or gravity.It was those insects that arrived first in your port. Our classification scheme made during my aftershock became a world itself, a procedure that was defined after it had happened. It was a fidelity of information that could only ascribe the certainty of persistent learning, a final becoming of what one so deeply desired. A difficulty in routine. I saw you weeks later on the TV screen at the deli, on a show filled with gleaming smiles, taut faces and perpetual ticker. You looked tired, thin, with less hair and more gravitas. The reporter asked your opinion on the plight that was at full rage in all known urban areas of North America. My eyes were ready for the invasion in sunny California, where endless summer and relentless beauty overwhelmed my walks and daily reckonings. New York was first hit the hardest – a glowing light in all street trees on darkened winter days to evenings: persistent radiance. I imagined you from the confines of a light drenched “day”, I wrote all that I could follow, sending you messy notes on maps, telling you it was the geography of will that could only manifest such an insect plague. An alienation of latitude, a degree of material difference in fate that marked us unable to comprehend emergence any more than the life of the pharoah ant or the dragonfly. We exhausted our reserves of trade, wrote: it would be enough to accept defeat from this false economy into the next period of unnamed exchange. It was my last letter to you that allowed me to forget our geographies and Linnaean schemes. You had stopped replying and I had found the perpetual light of evenings past, a blanket to sleep in periods of short duration. What did time or hours mean anymore, when I had forgotten dusk as a category and day as a known escape? We awaited your team’s verdict, exactly where Lux meridiani appeared or evolved from, and which numbered crate from a precise longitude or latitude it arose. My neighbors went on with their hours. There were no more lights inside houses, only black curtains drawn tightly. Pundits and scientists enjoyed showing satellite images of the world at “night”, composited into one gleaming beacon where every pixel of continent was white. Days of rain were welcomed as relief to our thirst for some darkness, some contrast in quiet. A year later, without any results, conclusions or reports with modest covers, you disappeared with all your notes and books. It was then I recalled clearly the first time you looked at me, lips curled asking if I only tolerated bad news. It was this bad news that made our fiction: The first time you kissed me next to the sundial, during the autumn when sundials still signified movement. A roccoco frame, gold, 4cm in width and height, shaded behind a velvet cloche. Olfactory dislocation, the ancient image of darkened alleys where mystery might have kept itself, a time when engines of recoding were somewhere between ecology and industry, and the rustle of plastic and tinny coos of zippers. A time when projections of desires still existed in the last coordinate of black. The melancholy of pleasure: placed between lines of parameters, poetry and disaster.

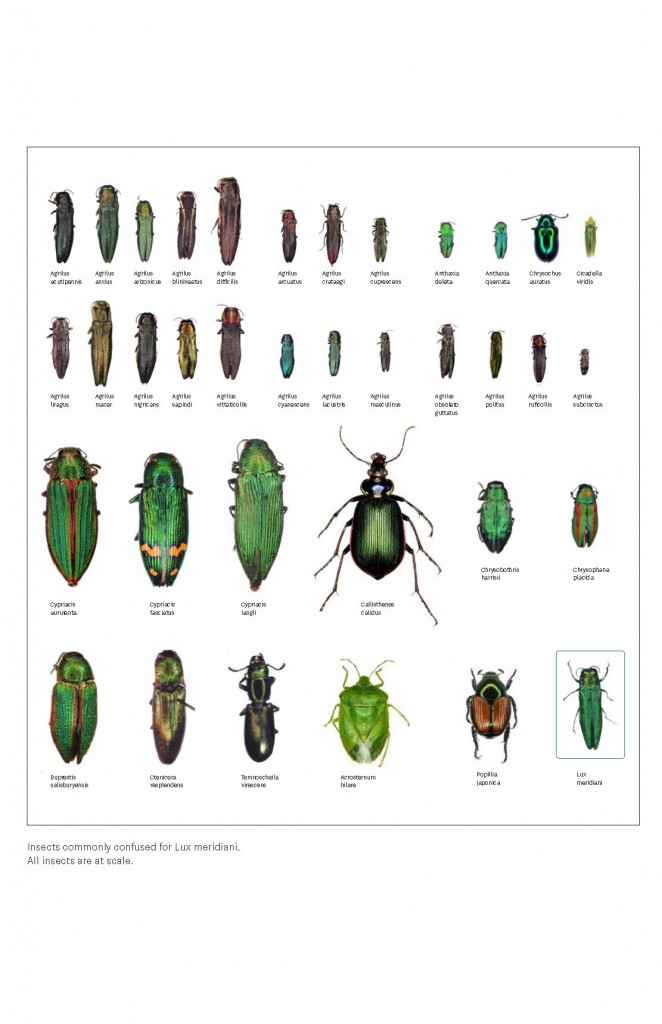

“Knowing is not naming” This workshop/teach-in will focus on the notion of the Anthropocene and the underpinnings of environmental change as a geographical issue, generated by the tension between classification, remote sensing and ground truthing. Through specific case studies of “natural disasters”, we will look at the systems of land use classification and how ideology is embedded in these ways of categorizing and ordering nature. Beginning with the earliest botanical gardens as a method to classify novel fauna from imperial conquest to the technologic determinism that continues to imbue indices of urbanization and human extents, we will understand hierarchies created by floristic maps more deeply and develop new ways to reconfigure some of the most embedded categories we have towards land use. Lux meridiani accompanies this workshop as a cartographic fiction built on existing data. By playing with thresholds in the geographical data and reorienting certain land use classifications, Lux meridiani takes the continuous exchange of invasive insects through global trade to imagine the emergence of a new, unknown species that infests street trees in urban areas with relentless luminescence. In this fable, Lux meridiani explicitly states what has been happening all along; that the recoding of our environment has been an economic rather than ecological engine all along. DOWNLOAD ACCOMPANYING HIGH RESOLUTION SLIDES: Slide_1.jpg Slide_2.jpg Slide_3.jpg Slide_4.jpg Slide_5.jpg Slide_6.jpg Slide_7.jpg |