Fire in Her Belly Catalog Essay by Martabel Wasserman

|

I recently curated a show, Fire In Her Belly, at Maloney Fine Art in Culver City. I am including the catalog essay in RECAPS as a way to share the questions posed by the work with a larger virtual audience. I want to thank all of the artists I was in contact with for their patience and willingness to engage: Zoe Leonard, Connie Samaras, Clarissa Sligh, Annie Sprinkle, Beth Stephens, Julie Tolentino and Suzanne Wright, as well as the Estate of David Wonjnarowicz and P.P.O.W Gallery, Western Projects, Carol Jacobsen, Elan Greenwald, Colette Perold, Kellie Lanham, and Michael Maloney for making the exhibition possible. – MW FIRE IN HER BELLY featuring Ron Athey, GANG, Lisa Kahane, Robert Mapplethorpe, Paulette Nenner, Pussy Riot, Connie Samaras, Andres Serrano, Clarissa Sligh, Annie Sprinkle + Beth Stephens, Anita Steckel, Julie Tolentino, Ai Weiwei, and David Wonjnarowicz“We were trying to get under the cosmeticized skin of representation, not only in the mass media but also in art itself, to develop a more complex understanding of the connections between studio and street work, academic and populist writing, and all the stuff in between.”- Lucy Lippard, “Too Political? Forget It.”[i] “Who am I beyond this skin I am in? beyond this place where I’ve been changed?”- Kara Walker [ii] There is an art historical narrative of the culture wars that is relatively well rehearsed: it focuses on the battle staged over the National Endowment of the Arts (NEA). Senator Helms and his cronies tried to define and regulate obscenity on a path to eliminating federal funding for the arts to restore “family values” in the United States. Artists who were caught in the crossfire emerge as the key figures in this version of the story and the significant aesthetic, performative and theoretical challenges posed to right wing ideology are ascribed to the (undeniable) brilliance of only a select few. This approach has the inadvertent effect of reinscribing the legacy of Reaganomics and the individualism of the 1980s that the coalitional organizing of the time sought to counter. Some of the artists in the story of the culture wars emerged from the trenches of ACT UP; others did not. Nevertheless, this backdrop of coalitional politics is crucial to how dissent was articulated during this moment. The commodification of dissent by the market and the academy evacuates the charged conditions in which these subversive aesthetic and theoretical frameworks emerged. There have been significant formal innovations in the historiography of the culture wars to narrate the horizontal organizational structures, and emphasis the privileged place that bodies coming into contact with each other had within the movement. Ann Cvetkovich insisted we make space for affect in An Archive of Feeling. Jim Hubbard and Sarah Schulman’s The ACT UP Oral History Project is a collection of personal narratives that counteract the dominant tendency of narrating history through a singular disembodied voice. Additionally, both of these projects recognize the importance of feminism in the successes of ACT UP — a legacy that is often lost in art historical accounts of the time. Fire In Her Belly seeks to counteract the dominant art historical narrative of the culture wars, resurrecting images that have been obscured from feminist and queer histories alongside those that have been anointed as canonical, bridging time and space to point to the collective process of visualizing dissent. The exhibition is an attempt to insist upon the importance of feminism in the visual culture of the time, and to look at how contact – between bodies, social movements, and ideas – shaped the interventions that big names made in contemporary art. The beginning of the AIDS epidemic called for new ways of thinking about identity politics. In the trenches, activists knew the virus was transmitted through specific acts, not specific identities. Grassroots education about the transmission of HIV/AIDS focused on descriptions of acts, dislodging common practices from generalizations about identity: not all men who have sex with men identify as gay, for example, or not all users of intravenous drugs fit popularized descriptions of junkies. The necessary focus on the exchange of bodily fluids informed new thinking about the fluidity of identity itself. AIDS activists saw that bodies are not autonomous – that they change each other through contact. We are physically permeable but often oblivious to this materiality of the self because of the challenges our permeability poses to dominant ideas of the individual. The centrality of the body, both physically and theoretically, made space for the emergence of queer politics – a politics of non-normativity not bound to a fixed identity. In the 1995 theoretical investigation of ACT UP, Saint Foucault: Towards a Gay Hagiography, David Halprin articulated the utopian potential of queer as a rallying cry: ACT UP draws members of all constituencies affected by the AIDS catastrophe, creating a political movement that is genuinely queer insofar as that is broadly oppositional; AIDS activism links gay resistance and sexual politics with social mobilization around issues of race, gender, poverty, incarceration, intravenous drug use, prostitution, sex phobia, media representation, health care reform, immigration, law, medical research and the power and accountability of “experts.”” Halprin describes queer as all-encompassing of difference. But the gap between theory and practice, was, as it often is, a treacherous chasm to traverse. Halprin’s analysis of queer is reflective of the hopes of this period, but elides the difficulties of organizing across difference. Similar to popularized notions of the social movements of the 1960s, dissent and conflict that happened within AIDS activism are often overshadowed by an idealized picture of the movement’s potential. Commentators of social movements often fall in one of two equally destructive camps: on one hand, to over-idealize, and on the other, to over-criticize. When telling these stories, it is our job to account for the difficulties inherent in organizing, but also to find the real moments of hope upon which to graft new movements. [i] Ault, Julie, Brian Wallis, Marianne Weems, and Philip Yenawine. Art Matters: How the Culture Wars Changed America. New York: New York UP, 1999. Print.

[ii] “MoMA | Projects | 1999 | Conversations | Kara Walker.” MoMA | Projects | 1999 | Conversations | Kara Walker. N.p., 1999.

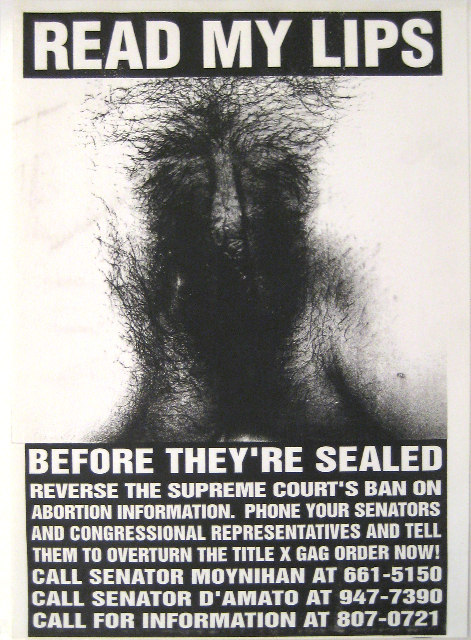

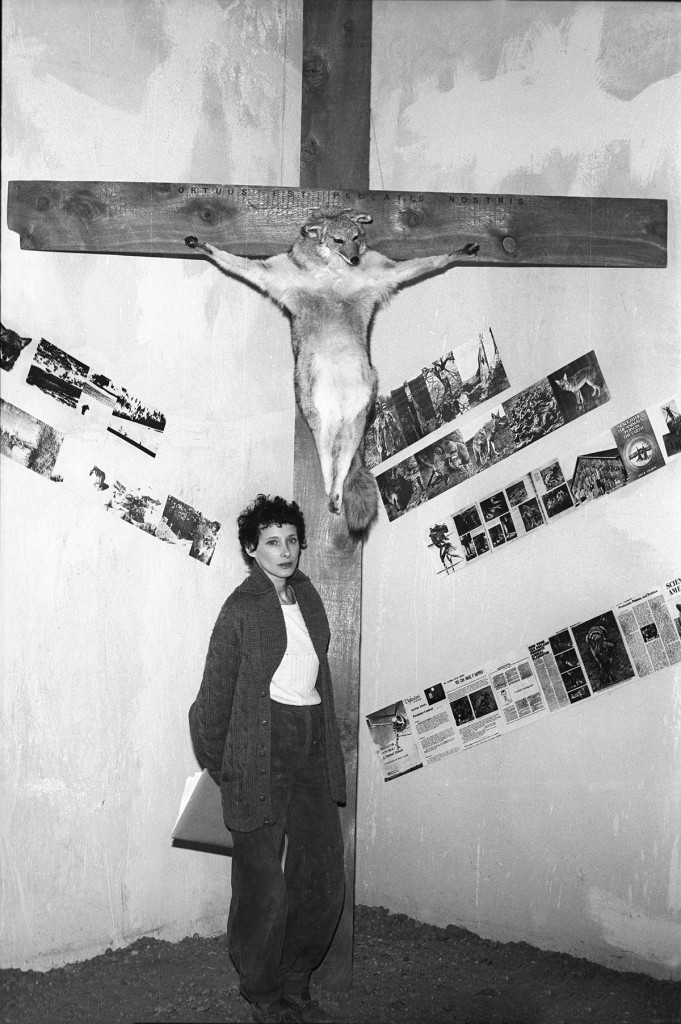

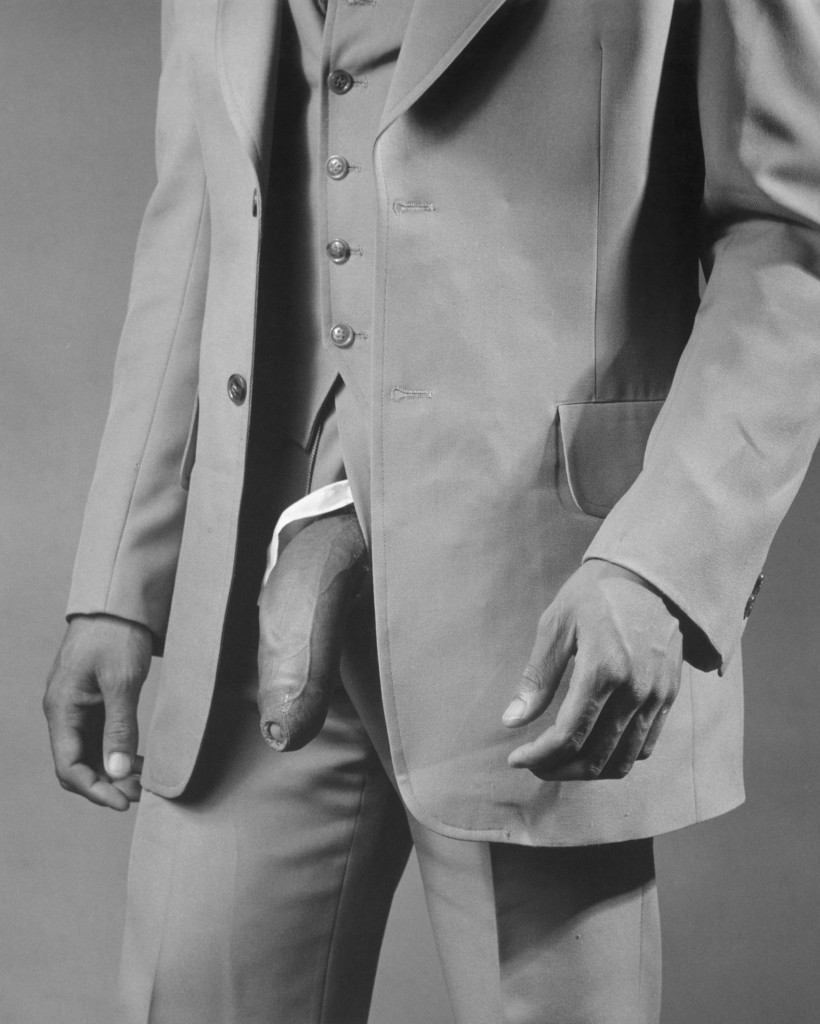

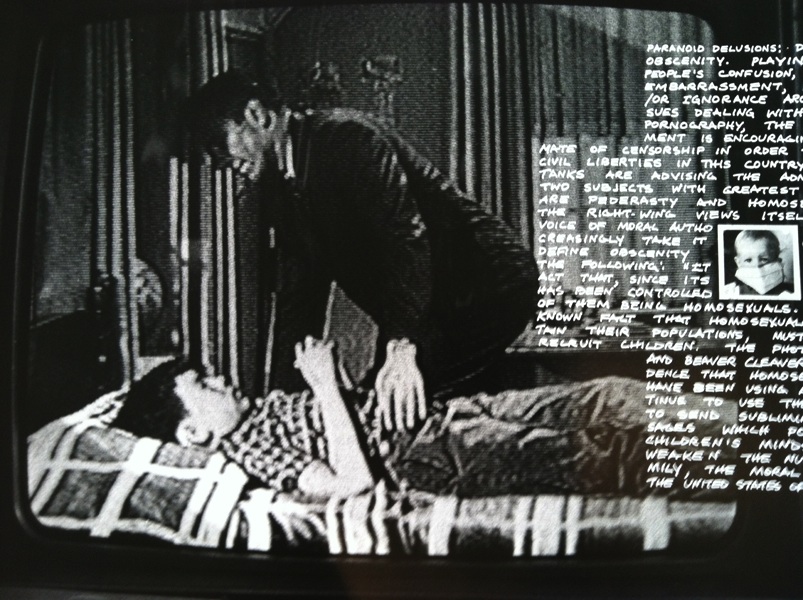

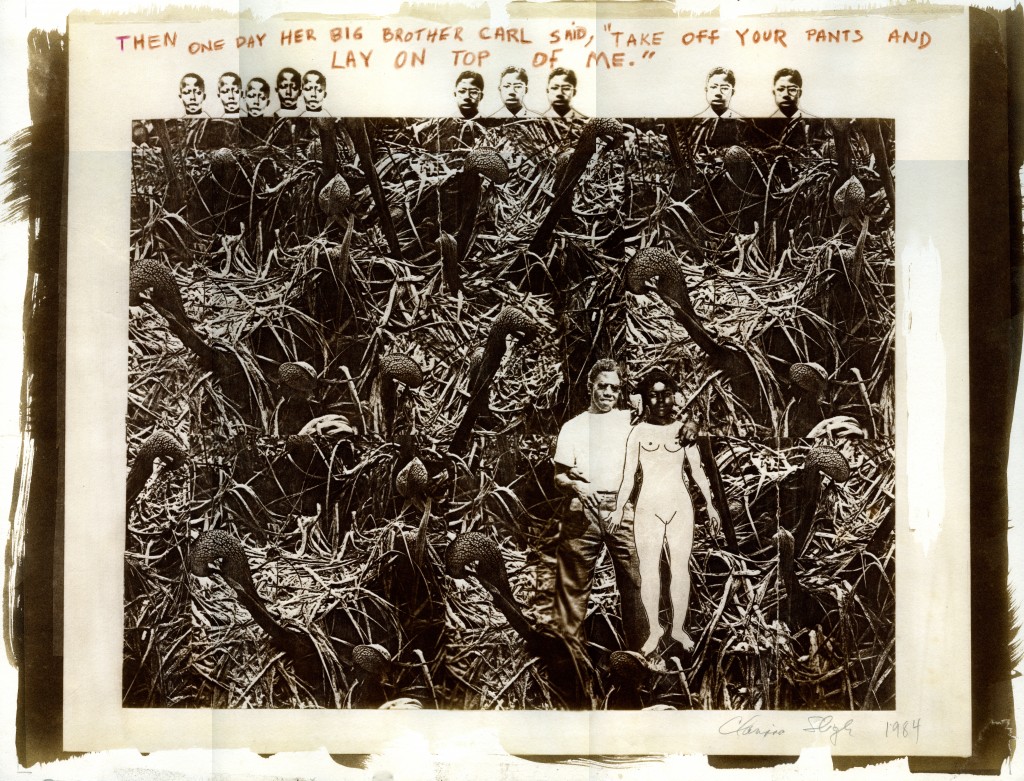

*** Read my lips. Bodies are battlegrounds. In wars waged over and through contested bodies, pain and pleasure become political fodder. Loss is collateral damage. Casualties are kept off the evening news, and wars linger on. If representation is not reclaimed, the risk is invisibility. Read my lips. Different types of bodies are policed differently, strategically obscuring how experiences of oppression are connected. It takes moments of crisis to make the connections clear; when the cultural pendulum swings so far right, coalitional politics between marginalized bodies becomes the only option. The early years of the AIDS crisis and the ensuing culture wars were one such moment. Feminists, leftists, queers, anti-racists and AIDS activists united in anger, sharing tactics for reclaiming representation, resources and rights. The AIDS crisis and the culture wars are ongoing, but the cultural and political landscape is bathed in the cheery glow of neoliberalism with the false promise of justice looming on the horizon. Appeasement divides us again. *** Paulette Nenner (1941-1987) was a committed feminist, animal rights, anti-imperialist and anti-censorship activist. In this photograph by Lisa Kahane, she is standing in front of her 1981 work “Crucified Coyote,” which was exhibited “Animals in the Arsenal.” It was censored and removed within a few hours of the show’s opening.She unsuccessfully sued the City of New York for the removal of the piece, citing the First Amendment. In 1982 her sculpture “Violated” which included a list of human assaults on the environment over an American flag, was covered with a cloth against her in will in “The Wild Art Show,” curated by Faith Ringgold at P.S . 1 for the Women’s Art Caucus. Like Connie Samaras, Anita Steckel Clarissa Sligh and Annie Sprinkle, Nenner was the subject of censorship by other feminists. Artist and scholar Carol Jacobsen has commented extensively on the complex relationship between feminism and censorship, including in her 1991 article “Redefining Censorship: A Feminist View,” from which “Fire in Her Belly” draws upon. Kahane’s photographs demonstrate the importance of archive-making. Her work, included the “WACK: Art and the Feminist Revolution!” (2006), has helped create an inventory of images of forgotten work that artists and activists are able to re-mobilize for the present. ***  Connie Samaras, Paranoid Delusions: Defining Obscenity (detail), ink, mylar, black and white photographs In her 1986-1989 series of photo collages, “Paranoid Delusions,” Connie Samaras addresses the circulation of misinformation by the right wing, scrawling seemingly unhinged text across the surface of popular media images. In one image she describes AIDS as a genocidal plot, using language eerily close to the calls of conservative senators to quarantine persons with AIDS (PWA). The photograph was removed from a 1985 exhibition at the Midland Center for the Arts in Michigan. As Carol Jacobsen writes, “the work was quietly quarantined without the artist’s knowledge—segregated from the rest of exhibition in a room with a warning sign—a form of mistreatment not unlike that to which people with AIDS have themselves been subjected.” Another work in the series, a collage of televisions with stills from the 1950s show “Leave it to Beaver,” states: “It is a well-known fact that homosexuals, in order to maintain their populations, must recruit and brainwash children. The photograph here of Ward and Beaver Cleaver is evidence that homosexuals have been using and continue to use the media to send subliminal messages which poison our children’s minds and weaken the nuclear family—the moral fiber of America.” Rather than shy away from right wing slander campaigns that conflated gayness and pedophilia, Samaras mimes them. Conservatives miss the joke. Read My Lips: leave it to beaver. *** Painter and provocateur Anita Steckel faced the consequences of representing her heterosexual desires within a culture of feminism where the phallus was taboo head-on. Steckel’s exhibition “The Sexual Politics of Feminist Art’ at Rockland Community College in 1973 created a local media frenzy, causing her to be denied a teaching position. That same year, she formed the Fight Censorship Group with her similarly contentious contemporaries Louise Bourgeois, Eunice Golden, Joan Semmel and Hannah Wilke among others. In the group’s founding document she wrote, “If the erect penis is not wholesome enough to go into museums, it should not be considered wholesome enough to go into women.”[1] The group created an archive of desire and the foundation of an argument from which anti-censorship feminists drew upon during the height of the sex wars about a decade later. Lust is central to Steckel’s representations of the phallus, but her work cannot easily be reduced to an exploration of the bodily. Steckel pointed to the relationship between capitalism, nationalism and patriarchy before the advent of women’s studies in the academy made such connections more readily available. Her paintings of erect penises over Manhattan high-rises in her Skyline Series ask us to consider how desire both implicates and liberates us from structures of power. Presidential Handshake was confiscated by the Fire Department from an exhibition at Collaborative Projects Inc. in Washington, D.C in 1983. The image, which depicts Ronald Regan gripping Hitler’s erect penis, illustrates Steckel’s uncanny ability to satirize the politics of desire. Steckel demonstrated how homophobia was a defense stemming from the deeply embedded role of homoeroticism in fascism and fascist aesthetics. Her depiction of the two men touching each other across time speaks to the deadly consequences of Reagan’s need to dictate desire on a national level. [1] Vitello, Paul. “Anita Steckel, Artist Who Created Erotic Works, Dies at 82.” The New York Times. N.p., 25 Mar. 2012. ***  Clarissa Sligh, "Then One Day Her Brother Said, "Take Off Your Pants and Lay on Top of Me," 1984, composite photograph Removed from a 1986 Women’s Art Caucus exhibition at Fordham University after Sligh refused to remove the text at the request of the gallery director. ***  Andres Serrano, "Piss Christ" 1987, cibachrome print, Edition of 10, 40 X 30 inches © Andres Serrano Piss Christ, the 1987 photograph of a plastic crucifix in the acidic day-glow bath of artist Andres Serrano’s urine, connected right wing anxieties about the exchange of bodily fluids, the emergence of fluid identity categories, and disintegration of the country’s moral fabric. Controversy surrounding the work, enacted what Richard Meyer has named the “Jesse Helms Theory of Art,” a theory that “teaches us that censorship cannot resist the images it claims to despise, and that efforts to suppress are typically fueled by its recirculation.”[1] As Meyer described, American Family Association (AFA) sent out one million letters describing Serrano’s piece, extending its audience far beyond the reach of Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art in Winston-Salem, North Carolina that awarded Serrano a $15,000 prize for the work in 1988. [1] Meyer, Richard. “The Jesse Helms Theory of Art.” October 104 (2003) *** Read her lips. Annie Sprinkle remains relatively unique in her crossover success in both pornography and the art world. Sprinkle is a beacon of hope for sex-positive feminists, using her experience in the sex industry to create videos and books about the complexities of female pleasure. She began her art career as a solo artist, best known for her “Public Cervix Announcement,” in which she inserts a speculum in her vagina and invites audience members to take a closer look. Sprinkle now collaborates with her partner Beth Stephens, spreading the doctrine of ecosexuality. Their queer approach to environmentalism has effectively linked how the construction of the good life is unsustainable for humans and the planet. Addressing representational voids, both together and as individuals, long precedes their important new work on mountaintop removal. The piece “1989/1992/2005” fuses together a 1989 video of “Public Cervix Announcement” with a sculpture of a speculum made by Stephens in 1992. Presented together in 2005, the retroactive collaboration speaks to the collective desire to produce new representations about women’s bodies and health before access to that information was a given. ***

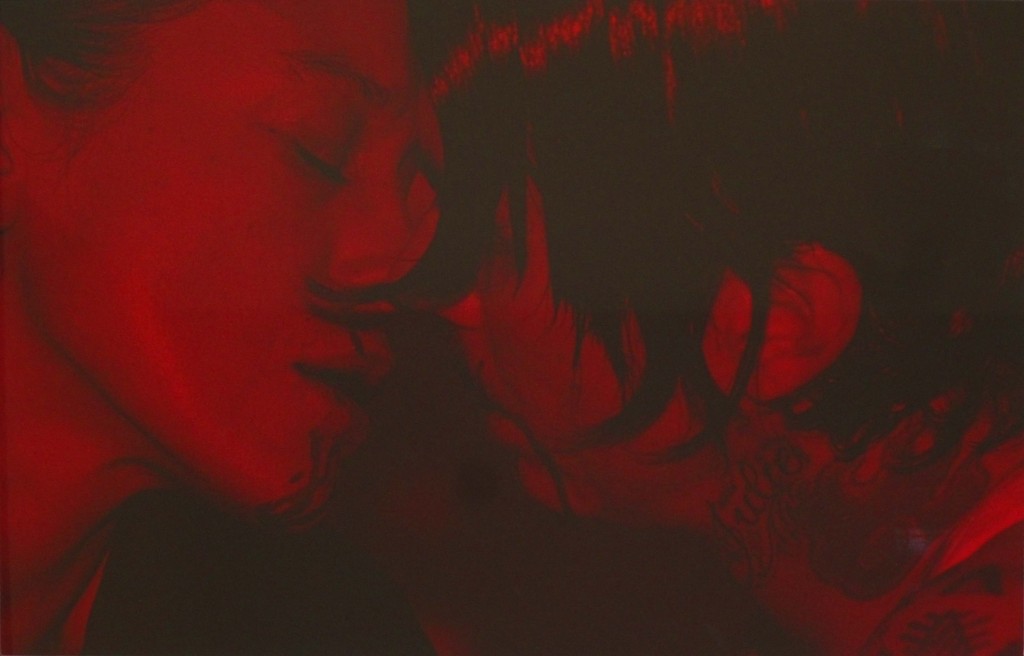

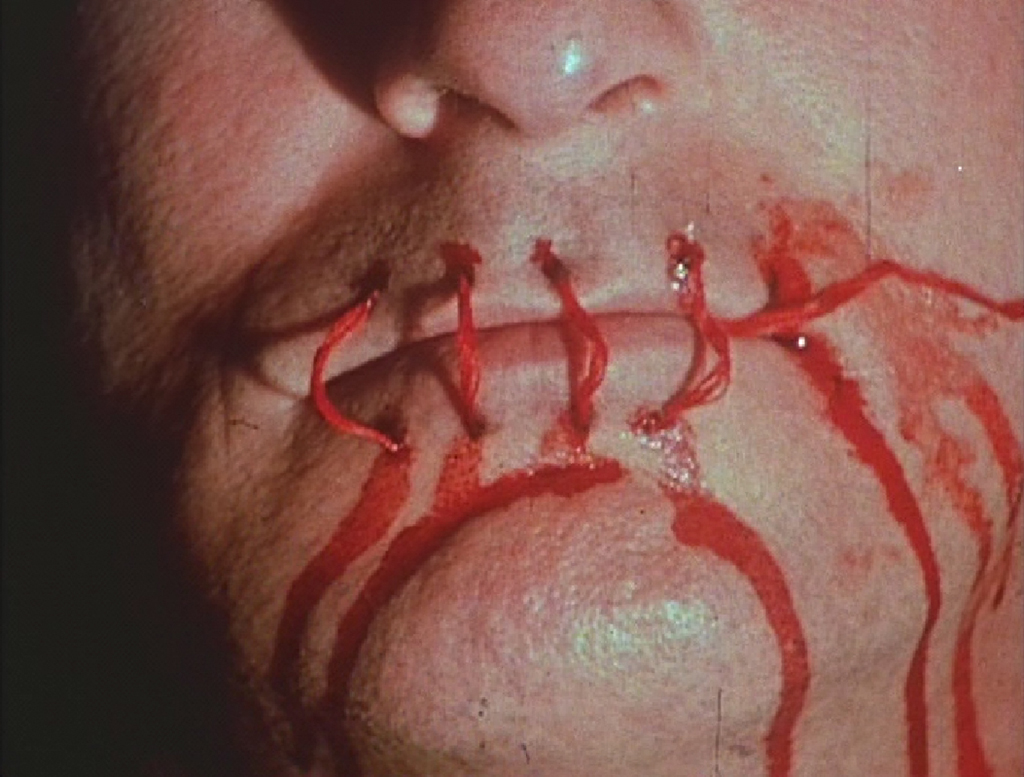

*** “If I could open your body and slip inside your skin and look out your eyes and forever have my lips fused with yours I would. It makes me weep to feel the history of your flesh beneath my hands in a time of so much loss. It makes me weep to feel the movement of your flesh beneath my palms as you twist and turn over to one side to create a series of gestures to reach up around my neck to draw me nearer. All these memories will be lost in time like tears in the rain” – David Wonjnarowicz The text is excerpted from a 1990 work, When I Put My Hands On Your Body. The description mourns the loss of an individual, a lover. It is silkscreened across the surface of skeletons in an image of excavated ruins, mourning the loss of a society, a tribe. Wonjnarowicz was taken by the epidemic 1992. What the does it feel like not to die with your comrades in battle, but to keep on living and fighting as the moment of impact recedes further into the catacombs of history? In Julie Tolentino’s on-going series of collaborations The Sky Remains the Same, she performs the pieces she has found most influential alongside her peers who originally performed them. In opposition to the reperformance impulse in contemporary art, which seeks to stabilize the meanings of work, Tolentino explores “how works may unbind/unwind/undo us as another form of history making.” Her performance Self-Obliteration with Ron Athey poignantly speaks to the questions of translating pain and desire across difference that Fire in Her Belly seeks to address. The performance begins with Athey, and later Tolentino, aggressively brushing a lush blond wig. When the performers remove the wigs, they reveal a set of pins on the underbelly of the acrylic blond mass that had been piercing their skulls as they brushed. Blood drips down. The prop, a sign of normative beauty and desire, stages drag that is specific to the gender, race and sexuality of each performer. In the second part of the performance, they each slide a pane of glass back and forth across their nude bodies. He is HIV-positive; she is not. He is a white man; she is a woman of color. They are both queer. Though performing the same action, their embodiment changes how the connotations of blood, nudity and pain are interpreted. Meaning is not transmitted between performers. Their queer exchange speaks to both the impossibility and necessity of solidarity.  Julie Tolentino "THE SKY REMAINS THE SAME: Ron Athey's Self Obliteration # 1," 2011, performance, photograph by Thomas Qualmann Solidarity, like love, is difficult by design. As forms of bonding, they point to the limits of empathy and the impossibility of understanding another human’s experience. Love is charged by the inevitability of loss. Solidarity is fueled by the optimism that organizing across difference is sustainable. While we can’t hope for a pure translation of experience, what we produce in the process of trying is the very material of radical transformation. ***

MALONEY FINE ART

2860 South La Cienega Boulvard, Los Angeles, CA 90034

310 570 6420

michael@maloneyfineart.com

|