Cruising the Archive with Ann Cvetkovich

|

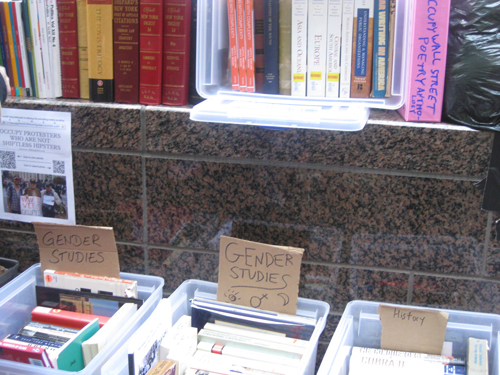

Cruising the Archive with Ann Cvetkovich : An Impromptu Salon with Kathryn Garcia, Catherine Lord and Martabel Wasserman In conjunction with the numerous site-specific installations and retrospectives happening in and around Los Angeles associated with Pacific Standard Time, David Frantz and Mia Locks curated Cruising The Archive: Queer Art and Culture in Los Angeles, 1945-1980, a generous three-part exhibition and catalog that is nothing short of giddy-making for those of us with a deep love for the material culture of LBGT history. As one exhibition in this project, Catherine Lord created a site-specific installation To Whom it May Concern at the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archive. Lord photographed hundred of dedications, drawing attention to this intimate yet public act of queer world-making. She then enlarged the photographs to encircle the very stacks she found them in. I met up with Catherine and Ann Cvetkovich at the archive for what proved to be a fascinating discussion about the generative possibilities of digging through the past, the politics of community and daily practices of resistance. AC: Its exciting to use this space as a staging ground for our conversation since I am hoping this evening at the panel [Queer Aesthetics and Archival Practices, January 24, 2012] we will be talking about what happens when artists go into archives and use them creatively. We are also going to be talking about the new partnership between USC and the grassroots ONE Archive. The university donated this space to ONE ten years ago but just this past year the collections have become part of the USC libraries. So it’s a very auspicious moment. It is not just a question of USC helping the grassroots archive, but a question of what the grassroots archive brings to the academy in terms of pushing the boundaries of what counts as an archive, what kind of knowledge can be created from it, and how that knowledge is created. I am especially interested in what artists can do because they bring a creative vision to archival collections. Coming to them with an aesthetic sensibility allows you to see new possibilities in the objects — to see print objects as, for example, tactile and material. And beautiful. MW: And sad. Or sexy. AC: Yes they are available to all kinds of investments. In my book An Archive of Feelings I talk about how can you archive feelings and also how can we let our feelings for the archive—our passions—help to inspire the knowledge we build from them. I went to the Mazer earlier today [the June Mazer Lesbian Archives at UCLA]. I love talking to the volunteers who work there, many of whom are not trained as archivists or librarians, but who donate their time to placing the materials lovingly into boxes and onto shelves. They have incredible knowledge because they have logged so many more hours than most scholars visiting for a project could ever do. The way they speak of the collections is not just full of information but full of love that contributes to the knowledge. MW: When I first read Archive of Feelings around 2009 it was a very different political moment than the one we are living in now. I felt some sort of phantom nostalgia for a moment of political action but also guilt, knowing that there was tremendous trauma that accompanied those moments of activism I longed for. I felt a very complex set of emotions around the archive. I was working with material on ACT UP, thinking about how to convey both trauma and the joy of resistance in ways that would resonate with me and my peers. Since that project, a lot has changed because of this surge of activism on a global scale. I hear a lot of people talking about “the new” in terms of political tactics. But having studied histories of activism I think it’s important to see how these threads and moments of utopian possibility are always present AC: I agree that there are always forms of activism going on, or if there is ebb, that they come back again. I myself feel like I belong to a somewhat belated generation because I am literally a child of the 60s and the 70s. I was a kid during that period of activism. I lived in the shadow of those social movements and had my own sense of belatedness when I got to college and the Vietnam War had just ended, and Carter had just been elected. It was a low ebb moment for activism. One of my first real moments of campus activism was the divestment movement of the 80s, which then morphed into my work with AIDS activism. I always felt the dialogue back and forth between movements. One of the things that excites me about your work is that you are thinking about what’s going on now as it relates to what happened then. I remember, for example, rolling up to a small protest on my graduate school campus, Cornell, and people were singing songs from the civil rights movement. I remember thinking, “Am I going to join in?” I was a little bit shy and I was also feeling like it was a very small version of past protests. But it was really important to make the leap and just say this is happening now and I am going to participate without necessarily having to judge whether it’s big enough, good enough, now enough, or real enough. Instead you can just let yourself participate in those moments and allow them to take you up. MW: I would like to talk about those kinds of moments, the moment of losing yourself in a collective body. In the institutional spaces of art and academia, it’s always about the individual and differentiating yourself. Or at least that’s how I experience it as a young person trying to jump into the conversation. It contrasts so starkly with that exciting experience of losing yourself in a crowd. AC: That’s a great way to describe it. I’ve been thinking about the concept of ecstasy as a mode of embodiment because I have a friend writing about it. As an academic, you are so often in your head, but looking for ways to get into the body. I think a lot about what it means to be embodied. Ecstasy is about being larger than or outside of your body, which can happen when you feel connected to other people. Like you, I am a big fan of collectivity. It’s one of the reasons I love demonstrations. Even if they don’t lead to an obvious result, I think they are meaningful as an embodied experience. In my interviews with AIDS activists in ACT UP, there is a lot of discussion of how exciting meetings can be: the planning or preparing for an event can be meaningful in and of itself. Thinking about forms of political participation that are embodied or collective has led me to think about the importance of bringing the sociabilities of art practices into political view. I had a chance to see the Occupy Wall Street encampment a couple of times this fall, and I was struck by the similarities to the Michigan Women’s Music Festival where I work in the kitchen every summer in order to have the experience of living in an intentional community. There were a bunch of people who had set up tarps and blankets (no tents allowed!) in order to make a community happen in the middle of New York City. Many of the things they needed to have to make that community were familiar to me from my experiences in Michigan. At the center or heart of the space is food and a place to prepare it. They were washing their dishes the same way we do it at Michigan, with three plastic tubs: one for soapy water, one for rinse water, one for bleach water. In addition to places for everyone to meet and also, as many people have remarked on, a lending library, there was a sanitation area with brooms and cleaning supplies.

CL: When I was there they had a women’s needs station, a space particularly for women.

AC: There were definitely questions about how the space might need to be semi-segregated to reach different constituencies. There was an altar and a sacred space.

MW: In L.A. there was the meditation tent, which was next to the People’s Collective University. There were all these spaces to address people’s needs. You don’t really think of that when you think of protest. AC: Right—at the Occupy sites, it was a big deal for people just to live in a community together. To me that implicitly addresses the criticisms about there not being a list of demands. I agree with those who suggested that the refusal to articulate demands was actually a smart move on the part of the Occupy movement. It was an end in and of itself for people to come together in that way. If I had had more time I would have happily camped out there for a while to experience that sense of making connections. Or even the problems making connections, because I could see that there was friction. I am familiar with that from living in community with people. MW: So it’s not this scary thing. AC: It doesn’t scare me to be in a group, and I also don’t romanticize it. I know it’s actually really hard to walk into a collective and try to find your place in it. But it is also very valuable, whether for shorter or longer periods. The feelings of activism and collectivity have been a very profound part of the new work I have been doing on political depression. My work has always been about what it means to make space for political feelings but I wanted to make even more space to explore the messier feelings produced by political life. In tandem with that question, I wanted to keep asking about the place of culture and art, which sometimes gets sidelined as frivolous, or not enough, or secondary to the “real” work of politics. There has been a tremendous amount of really fantastic thinking on cultural activism — in the AIDS activist movement, for example. It’s not just specific to that movement but there was a lot of powerful thinking about why culture matters to an activist movement in that context. Even though there are plenty of resources to draw on, there can still be that tendency to dismiss cultural expression. I always want to make space for that. And I always want to make space for people processing their shit [laughs]. You said you are interested in art-making that comes from or leads to collective practice, which is also very important to me. I am a big fan of the salon, a big fan of social relations. One of things that I love about these archives are the friendship networks and social relations that allow people to work in the world. (Catherine’s dedication project is a window onto them.) When you do research in queer archives you discover that behind every name or better-known name, there are always so many other names. Archives allow you to start tracking those friendships and connections. Those relationships are the foundation for the production of art and for a life well lived (which might be one of the best forms of art) – and, indeed, the ability to do anything in the world. Sociability is so precious. I love the queer ways of creating it, and I love figuring out how to document it. It is a resource for the present. I always want people to take their own connections seriously. There is a kind of political depression that can come from the sense of belatedness we discussed earlier: “they had this special set of relations and we don’t.” With respect to queer art worlds, for example, people will turn to Paris modernism in the 1920s with Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, Natalie Barney, Renée Vivien. People look to the 1950s in New York with the Beats and the abstract expressionists. Or later with Andy Warhol and the Factory. There is still a tremendous amount of scholarship to be done just to fully excavate those queer social worlds. But I want that work not to mystify those worlds but instead to provide enabling models for you and me having this conversation or for the conversations I have with my friends. We are having a salon right here, right now just as they had in Paris in the 20s, or in New York in the 50s and 60s. Everyone was important to those networks, not just the big famous dudes but also the minor figures who might have been running the camera [points to the lovely Kathy behind the camera] or doing their work in minor creative genres. Pacific Standard Time has been really great for demonstrating this because there have been exhibitions of furniture, ceramics, and the minor art practices and forms that don’t always get the attention of more celebrated fine art genres. Some of the artists came out of collective studio practices or school networks. The show at the Huntington about the furniture maker Sam Maloof is also about other artists who were part of a network centered around the Claremont colleges, and whose work is also an important part of the history of the LA art scene. Thinking about ways to document those kinds of networks is also really important. MW: So we have talked about embodiment as a way of theorizing, cooking together, dancing together, that sense of being there, like at the Michigan Women’s festival or OWS. Now that those encampments are gone there is a residue that is both physical and virtual. I wanted to ask you about how you think virtual community is functioning in relationship to embodied networks. AC: I have a strong preference, a love even, for the embodied, face-to-face connection. But I don’t want to make a strict division between the virtual and the actual because I see how the virtual enables all sorts of physicalities. It’s a resource and a tool. My worlds are so dispersed. I have my friends in Austin, but the nature of being an academic is to have community all over the place, including my former students. We communicate back and forth via virtual means, such as Facebook and email. It can be great to be able to collaborate with someone and not actually be in the same place, to send words back and forth to each other. At the same time, I have had a great time being in L.A. the past couple of days, seeing people I don’t normally get to see. With the encounters in person, you get to work on the connections so that they can energize you or you can make something happen — you take that inspiration and work with it. The direct contact is sustaining. It helps with those moments when you can feel very alone, whether it’s because you are in front of your computer having to do your work or because there are no parties happening or you are tired [laughs] … and then you can be nurtured by that sense of virtual connection. I saw this amazing artifact at the Mazer archive, a wall screen by a woman named Ester Bentley titled “Celebrating The Women In My Life.” She collaged together images of her friends with writing that said things like “I Am A Composite Of All Those Who Have Touched My Life,” “See All Your Relationships as Sacred and They Will Mirror Your Soul,” “Each Picture Will Be To the Last A Fleeting Moment Rescued From the Past.” CL: This is so you Martabel. MW: I just want to make work about loving my friends. That is what RECAPS is. AC: I too work that way. I have had this long-standing exercise for myself that came out of a writing workshop where the facilitator asked us to write our own obituaries as a way to articulate our deepest goals. Of course I have ambitions for this book or that creative project but I realized I just wanted to be known for having a lot of friends and being loved by a lot of people –for having made connections with a lot of people. That is what I find sustaining and it’s something you can make happen in most times and places. I just had a little salon at my house because I hadn’t had a chance to really acknowledge finishing my book manuscript. I wanted to have a ritual of some kind to mark letting it go into the world. I pulled a small group of people together, and we did a little writing exercise about what letting go meant to everybody. I looked at the faces of the people gathered around me, and I said I am going to try to remember this energy, this collectivity, so I can have the courage to put this work out there. Let me say one more thing about embodiment and political depression. In the book I’ve just finished, I tried to think about depression as the residue of long-term histories of violence. I think of our bodies as this site of weight-bearing. If you think of yourself as a sensory body who is feeling the atmosphere around you when you are connecting with people in a room, sometimes you carry their heavy energy as much as you are buoyed up by their joyous energy. We are a sensitive interface with the world. We are carrying historical residues, collective residues. I’ve been thinking about racism and sexism and homophobia as these things we are carrying in our bodies from previous generations, whether from our families, our own experiences, or the fact that the world that we live in is physically shaped by histories of violence. You can choose to open yourself up to feeling that. That stuff is inside of you, but what does it mean to try to notice that? It can freak you out and bring you down [laughs]. It can be a very heavy weight. For a white person, for example, to actually be open to hearing the experiences of everyday racism that even my middle-class black academic colleagues face. To me, political depression is about accountability to those multiple generations, a way of bearing that weight and then also moving it—someway, somehow. We are in relation to history that we can choose to be open to and aware of. As a younger person, you have the responsibility to carry those histories forward. But I like to see how intergenerational connections can be as enabling as possible. How can older people share their experiences, but not in a resentful way like “you’re not listening to us,” or “we did it better.” There are a lot of traps and it’s important for young people to be respectful but also to make it up in their own way for their own time. One thing I liked about your ACT UP project was that, as an older person, I was really gratified to see a young person who was really moved and inspired by AIDS activism but who was also not afraid to point out the places where the cross-generational connection was not happening. CL: It seems to me, being an older person trying to listen to people who are younger—I mean really listening, apprehending almost physically—this kind of rage or disappointment is just as important as the other way around. There is something about aging and the embodiment of your body in conversation with someone in a much younger body. I feel very conscious of that. AC: I did another salon when I turned fifty to try to explore what aging is. One of my slogans was “50 really is 50.” I didn’t want to say “50 is the new 40”; I really wanted to acknowledge aging. I ended up, not surprisingly, thinking about trauma and wounding. By the time you get to be 50, you’re going to have some wounds, and my wish coming out of that discussion was to have the wounds of aging make me bigger not smaller. … Your body does change though. CL: Right—so how do you keep your mind open when your body is going to have those limitations? AC: I think you are picking up on something that I will have to keep practicing: how to really listen to younger people. I always want to be honest about the difficulty of meeting a goal like that rather than just saying, “do this.” It’s one of the problems of a politics that thinks it knows the answer. It should be about a practice. What is the practice of listening? KG: There is also the legacy of the mother queer culture. My friend Flawless Sabrina, who is one of the oldest drag queens, calls all of us his children, his granddaughters. I learned that he dated William Boroughs and he always says Bill is the one that taught him how to be an old fart. He dated him when he was very young and Bill was already old. Because the community is so at risk and a lot of people don’t have families because of their sexual choices, there is this alternate tradition of learning from your elders. So you start to create families that aren’t hierarchical in the same way as the one you came from and you develop relationships with mentors who think of you as their children. You learn from them but they gain so much from you too. They can feed off your vitality and youthfulness; you are blowing their mind in the same way they are yours. Flawless sees someone like Zachary Drucker and how different their experiences are doing drag and being trans. Those relationships become very symbiotic. I always think of him because there are other practices of mine where I have mentors and there is this kind of inevitable power structure where they just think because you are younger you don’t really know what’s going on. Flawless is like, you are younger than me and you are teaching me everything. That is how I would love to age: to maintain that kind of openness. CL: Teaching, structurally, is someone who is older talking to people who are younger. That is the institution. How do you consciously undo and resist that? How do you actually shut up and listen or learn how to ask questions? There are an incredible number of dedications in the archive to teachers, and fewer to students. But there are some. There is that thread of relationships throughout the dedications. It’s a trope of moving queer culture along. KG: I think you learn a lot from being someone’s teacher. AC: Absolutely. What you just described is a very lovely vision for that kind of cross-generational education and practice of listening. It’s interesting to think about where and how that happens when we are teaching inside of academic institutions. I want to picture not just an ideal model, but also really pay attention to the places where it’s not happening. For example I’ve tried to notice the places where I feel threatened by younger people. I was shocked when I first noticed that inside of me. CL: Yup. AC: I was always thought that would never happen to me because I knew it was a problem. And then you have to contend with it. MW: How do you identify those feelings, own them, and move forward? AC: You mentioned mothers. The trope of repudiating the mother in order to be who you are has been a big issue for feminism. We’ve tried to craft modes of feminist teaching that create different kinds of relations between teachers and students, but sometimes there are new problems that are created as you are trying to resolve other ones. It can sometimes feel like too much to do the work of mentoring that we’ve tried to do in more hands-on and supportive ways. I can’t always provide everything I feel I am being asked to do or feel like I should do. The burden of professionalism and institutionalization within the academy sometimes means you run the risk of burnout. The delicate feelings of mentoring relationships can get weighted down by the way the institution works. The challenge is how to free up the relationships so that their emotional energies stay in good shape. And listening. I’ve done a lot of work on the practice of listening; I take that to be a bedrock lesson of feminism. I am a pretty die-hard enthusiast of consciousness-raising as a model. I want to name that as an influence for all kinds of different practices of community building and of teaching and so on. Listening is a practice. It’s a lifelong practice: noticing where you are not listening, maybe just because you are tired and not paying attention, but also where you are not listening because someone’s shit is bugging you and you don’t do well with listening to that kind of person. Continuing to learn how to listen is a fundamental building block both for creative and personal relationships. MW: What do you think it means to take risk in the academy? AC: I visited a women’s studies seminar and one of the students asked me how I had the courage to write my Archive of Feelings book. The question really took me by surprise, and I paused and then burst into tears. I didn’t feel like I had been courageous in writing that book; I was just doing what felt meaningful to me. I was very touched that someone thought I had been courageous and then a little sad that I couldn’t recognize it as such. Afterwards I realized that maybe it’s because we don’t understand what courage feels like. I am trying to remember that as I stand on the brink of publishing this new book on depression. I’m terrified about it—I feel like it’s stupid, the writing is bad, it’s too personal. But I need to remember that it is an act of bravery to be persistent in the face of feeling bad about ourselves. I am interested in thinking about depression in terms of everyday feelings like the self-hatred that we are often weighed down by. The battle against those feelings is also part of the battle against larger systemic violence. That’s where political depression lies. It is very physical for me. Building everyday habits of survival is a practice that will move us forward. The use of art, or listening, or whatever tools we have to craft or create sociability is really important, whether it’s just on a small intimate scale or morphs into something larger. Ann Cvetkovich is author of An Archive of Feelings of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality and Lesbian Public Cultures (Duke University Press, 2003) and Depression: A Public Feelings Project (Duke University Press, 2012 forthcoming). Visit http://www.utexas.edu/cola/depts/english/faculty/ac446 or www.anarchiveoffeelings.wordpress.com.

|