Radio, Paradise, and Nuclear Power: Kaucyila Brooke interviewed by Christina Linorter

|

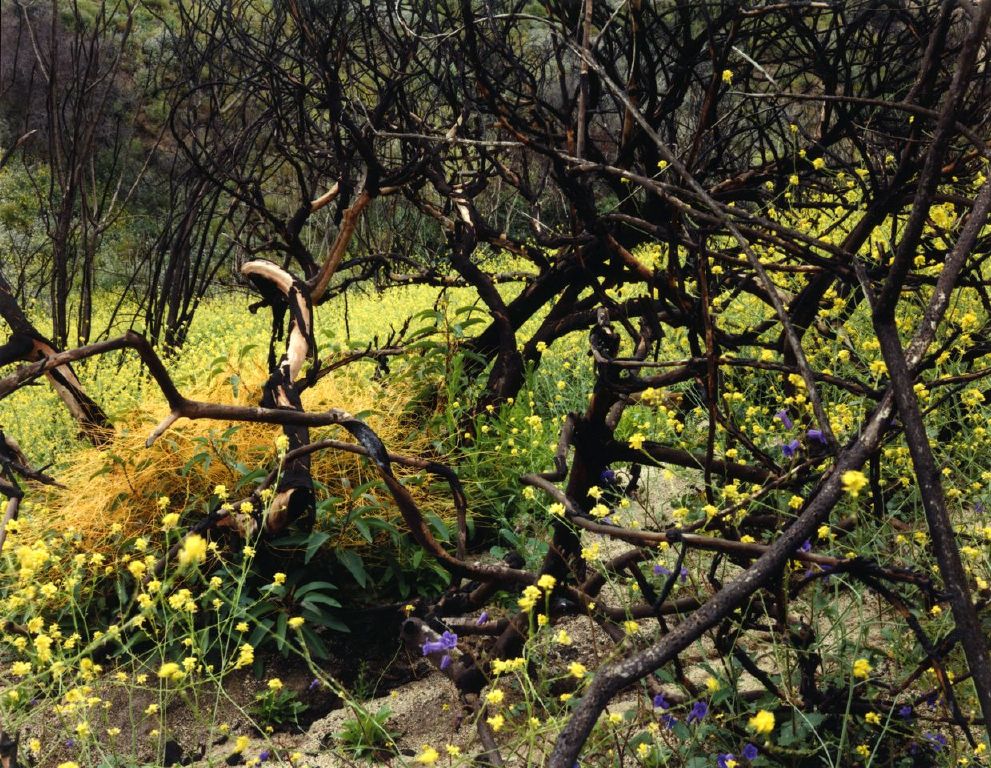

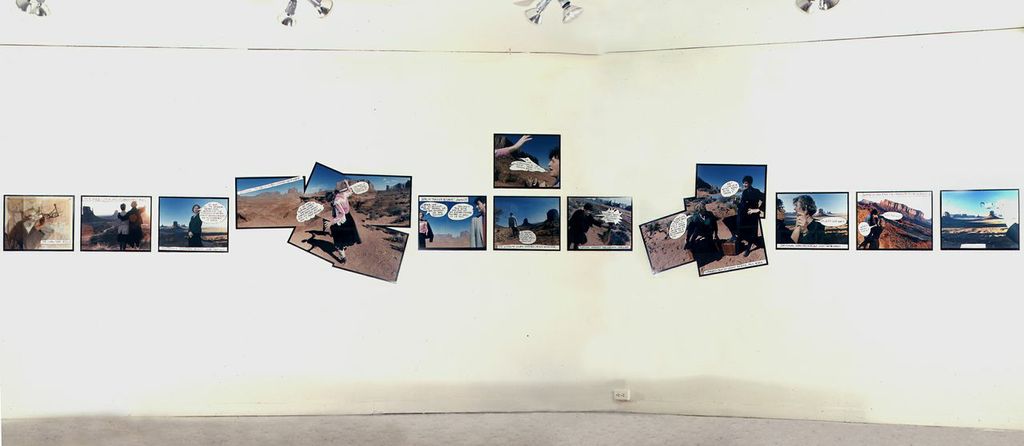

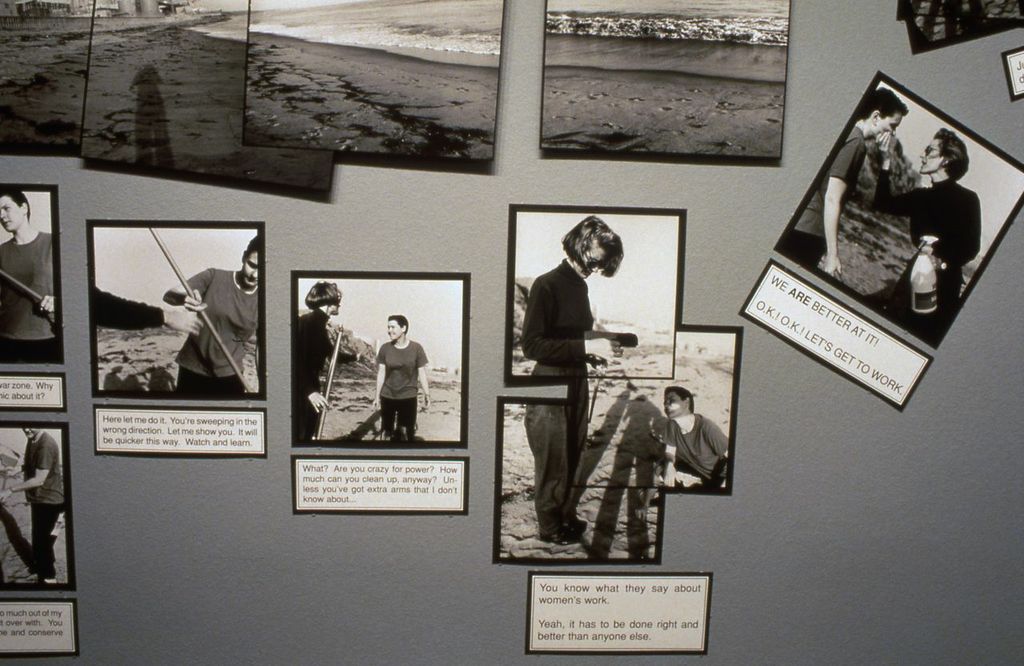

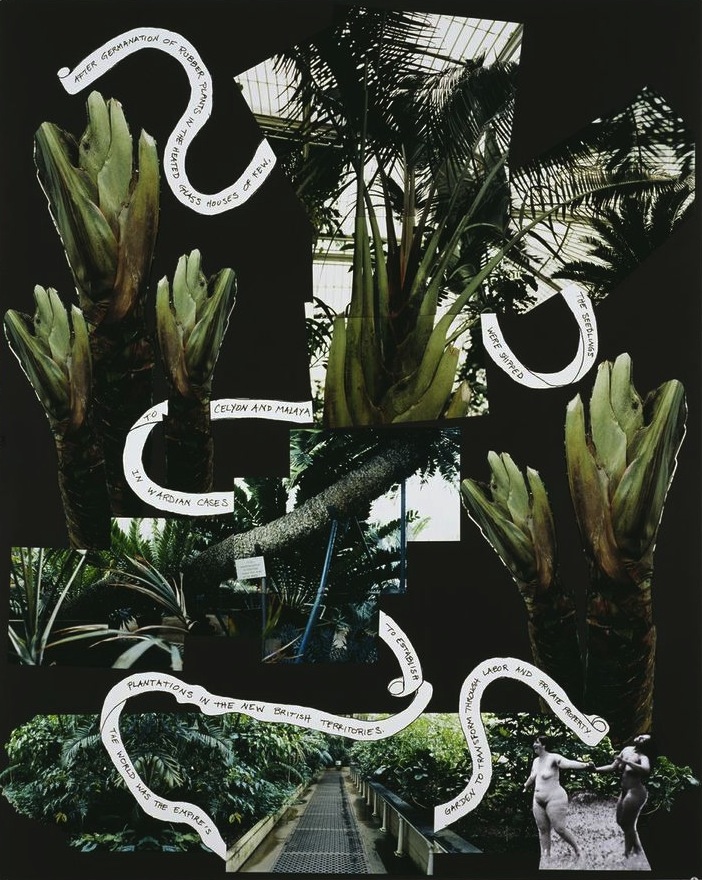

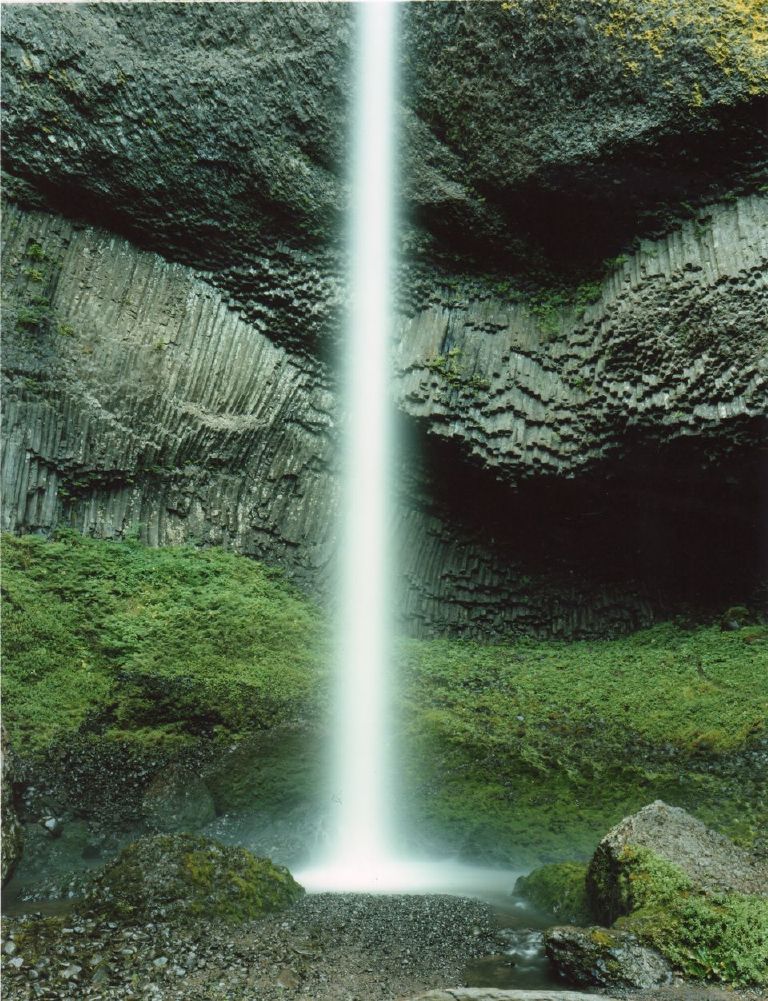

Politics and Narratives in Landscape and Gardens[1]CL: In the Eden’s Edge project we are specifically interested in the relationship of narrative and landscape. In your work you combine exactly these two themes. How did you become interested in using narrative as a tool for your art practice? KB: I guess I was always attracted to a sequence of images rather than single images. And really that had to do with my not accepting the tendency within modernist photography to find some kind of perfectly resolved expression or sort of idealized objective form as did a lot of photographers who were the masters of the Modernist canon of fine art photography education. Cartier-Bresson had this idea about the decisive moment, when the precise vision of the photographer perceived the moment that all objects came into the frame formally and made a meaning that wouldn’t be available a moment before or a moment after. Edward Weston too was always looking for the idealized form that would resolve the problems of content and form. And Ansel Adams separated continuous-tone black-and-white photography into twelve zones so that the master photographer could compose a score and perform an idealized representation of nature, which was ultimately an articulation of nineteenth-century ideas about nature and representation. I think that the sequence already disturbs all of those ideas because it’s not a matter of editing down to the one essential image, but rather it’s a matter of an accumulative meaning when you move from one frame or fragment to the next. I often think about the inadequacy of the single image to carry the contradictions that are in dialogue with each other to activate meaning. I have always been engaged with narrative. I was an English literature major in college and, as a kid, I had a comic book collection. As much as I love literature and considered becoming a writer, I always felt limited by what a text looks like on a page without pictures. I just found it disappointing when I looked at the books that my parents were reading, and they didn’t have any pictures on the pages. Then as a literature student, I studied William Blake, for example, who combined image and text. At the time, there were few representations of Blake’s work with image and text. His poetry was often printed as text only and the same with his visual works. I think Modernist literary criticism couldn’t embrace this hybrid practice, so it focused instead on one or the other. I was also excited by medieval art because in it, I recognized, was the implicit importance of sequence and narrative. Those are some of the reasons why narrative was important to me. Later, I became more engaged with structuralist theory. The structure of narratives is like an outline of a series of ideas. And certainly from the position of analyzing the text, which, of course, is my early intellectual training, one always looks at the structure that the text fits into, how it articulates itself. So I continued my research in literature by working with different genres and experimenting with different genres of narratives. For example, in the 1970s, I was a radio producer of feminist radio programming in Columbia, Missouri, at an anarchist radio station called KOPN FM. We had an idea of media that was the opposite of a generalized, sound- bite media culture. We had block programming, and all programmers experimented with how to produce radio. Lorenzo Milam’s text Sex and Broadcasting was partially our inspiration and textbook. A good example of that is that every Saturday morning, there was this guy who read Greek drama on the air, which is so eccentric, right? He would sort of stand in the control room and read and gesture, while at home you would listen to Antigone or The Odyssey as your were starting your Saturday. So I used my feminist radio program as a way to extend my research on women writers and women in literature because when I was in college we basically read all male authors, and I wanted to fill in the gaps in my education. I did a radio program on Gertrude Stein, I did a radio program on Virginia Woolf, one on Colette, etc. I continued the research that I learned to do as an undergraduate for my work in radio. And once I became a visual artist, I continued to explore historical ideas about narrative. CL: When or how did ideas of landscape enter and become important to your work? And do you think that a narrative always contains a landscape? KB: I had an affinity for nature and landscape early on. I grew up in the state of Oregon, a very beautiful area of the country with volcanic mountains, rushing streams, waterfalls everywhere, and a gorgeous wild coastline. My parents loved bird-watching and exploring the landscape – particularly my father, who was a native Oregonian, a fly fisherman, hiker, and, at one point, he was on the State Game Commission. When you spend a lot of time in landscapes, of course, you realize that they are political spaces. They are not spaces that are devoid of people or of the influence of people. Much of how landscape is discussed has to do with access to it, land use decisions that are made around it, people who make their living from it, and how they are affected by legislation or governmental policies and decisions. When I started working on sequential narrative projects, of course, I would photograph my characters in both interior and exterior spaces. And although the “background” was significant to the subject of the piece, I was not specifically dealing with issues about nature or landscape. The first piece that I made that addressed the landscape was This Land is Your Land, which I made in Monument Valley, Utah. At the time, 1986, I had been watching a lot of John Ford films. John Ford is very specific in the way that he deals with nature in his narratives. For him, the landscape really is symbolic, in the background, representing something greater than the heroes and anti-heroes of his films – a space of mythic proportions. He isn’t realistic at all, and he moves all his characters through a fantasy landscape, which becomes another character in the film. And as I looked more and more at Ford’s monumental historical narratives, I realized that there wasn’t any place for woman’s desire as an active force in the stories. It was really masculine desire that fueled the actions of the narratives against this grand landscape. The women characters were certainly responsive, integral, and affected by the actions of the male characters, but they were only allowed to respond, not ever to actualize anything. I took some friends to Monument Valley, and I photographed them in this landscape. And I had them wearing costumes, referring somehow to the West and also to an urban context. I wanted to talk about the stickiness of a narrative in a way that you can’t separate yourself from it and you can’t completely connect yourself to it, like this dust that gets everywhere. So there is a possibility of changing the narrative without you going outside of the narrative; you are always implicated in it, whatever position you take in relationship to it. This Land Is Your Land is a sequence of multiple color photomontage panels in which the women characters discuss their relationship to the narrative of the Western landscape. It was the first time that I made a piece that tried to talk about an existing narrative and how it functions in relationship to a landscape. After that, I made a piece called Not Lying Down, which was four layers of color-coded narratives discussing the power dynamics and process of trying to come to agreement through consensus decision making. So it’s about all these people working together to try and make a decision together. One of the narratives involves a couple in a bed, and they are talking about the political power issues in their relationship. As they are having this pillow talk or bed conversation, the location of their bed changes. They start out sitting in the bed in the blank space of a studio, against the seemingly empty and seamless background of the studio. At some point, their bed is in an empty bed-room, so it’s actually in a domestic space, and they continue to talk about domination and subordination, dynamics in politics, as well as in their relationship. At a certain point, their bed is in the desert in the Saguaro National Park near Tucson, Arizona, and there they talk about the concept of natural power positions and question the naturalness of masculine and feminine roles. It is a bit like a passion play or a simple illustrative gesture because the moment when they bring nature into their conversation is also the frame in the sequence when the background transforms into a natural landscape. I started dealing with landscape more structurally in that particular piece, and that’s when I started thinking about the way we talk about human nature. We talk about it as if we all know it, even though we are arguing about it all the time and what that has to do with gender and sexuality. So nature as a background through which characters in conversations try to figure out their position in the narrative space then became a major motif and structuring device in my work at that time, in 1988. In 1989, I continued the project of commenting on classic and idiosyncratically selected narratives with a piece called Making the Most of Your Backyard: The Story Behind an Ideal Beauty. I started thinking about a narrative called Le Roman de la Rose, or The Romance of the Rose, which was written by the French poet Guillaume de Lorris in the twelfth century. It’s an allegorical poem that presents the ethics of courtly love, and it traces the story of a dreamer who falls asleep in a garden and looks into Narcissus’ pool. He falls in love with the first thing that he beholds after he sees his reflection, and that is a rose. The narrative is said to be the first romantic narrative in Western literature. And, of course, it’s a heterosexual narrative, and it’s all about the dreamer’s desire for a rose and the impossibility of obtaining his love, which is surrounded by a cage of thorns. I became curious about the garden and how it functions in this first romance narrative. I thought maybe that would be a place to talk about desire for the other since there is already the built-in distance between the lover and his love object in courtly love. I took it on as a way to explore beauty and harmony and the ethics of projection of desire onto the other. I also wanted to explore where lesbian desire fits within that because there is this old idea from the early part of the twentieth century that homosexuality is narcissism, or that two men or two women loving each other is a kind of arrested stage of development because they haven’t moved on from a narcissistic stage of development. So that’s when a garden as a landscape of desire first enters the work. And then in 1991, I started looking at the Genesis story, which is an always-presumed heterosexual initiation of the creation of mankind. I started thinking, well, maybe another desire to look at is Eve’s desire for knowledge. I could take these two women characters and their curiosity, which is presumably the sin that Eve committed that launched us into this descent from the garden. And their curiosity could be the desire that fuels this particular narrative, and I could make a narrative that really investigated the way that concepts of nature function in different historical periods. Tit for Twat is the third in the trilogy of works that engage in the discourse of narrativizing women’s desire, and the characters Madam and Eve and their curiosity or desire for knowledge leads to questions of originary tales and the concept of nature. So, they go from a garden, to wilderness, to different historical gardens and how they externalized the cultural idea of nature and control of nature at these different time periods, and the idea of human nature. They try to figure out what makes them human and what makes them nature because this word nature means a lot of different things. CL.: I think this is an important point for what we are trying to do with the Eden’s Edge project –not asserting a preconfigured identity onto anything. By doing this, the landscape gets completely deconstructed, and it’s impossible to see it as unified anymore. So when looking at your work, it shows all these layers, but there is still a very political intention behind what you do. KB: Yeah, definitely. Another project that I made is called Thirteen Questions. I started that in 1989, and to date I have completed three of the Thirteen Questions. Thirteen Questions refers to a questionnaire for prospective roommates used in a collective household where I lived from the mid- to late 1970s.Whenever we looked for a new roommate, we would have a meeting, and we would establish a questionnaire that we would use for interviewing a potential roommate. We had thirteen questions on this questionnaire, and they were common questions, like “Are You Messy or Are You Neat?” and “Do You Like to Garden?” There was something that we called “The Food Question”, which was all about vegetarianism or working at a food co-op, and, because we lived in such a highly politicized community and things could become quite polarized, we also had questions like “Are You Politically Correct?” as a way to start the conversation about gender and social politics that were so important for living compatibility. Years later, starting in 1989, I thought the questions could be applied to the landscape as a way to think through global cohabitation and spatial and environmental negotiations. For Are You Messy or Are You Neat? I went to San Onofre Nuclear Power Generating Station, which is a power plant that sits right on San Onofre State Beach between Los Angeles and San Diego. I made a series of photo fragments and combined them into a segmented panoramic photograph of the power plant. The photographs are not stitched together as a seamless panorama, but all of the gaps are roughly outlined from the frames of the photograph so that the photomontage is evident. I took a couple of friends and had them act as characters there at the beach with brooms, mops, bleach, and other cleaning supplies. I wrote a text that was their dialogue that was basically about the politics of cleanliness. It refers to the proverb “A man may work from sun to sun, but a woman’s work is never done,” which always has to do with women cleaning, cooking, and managing all things having to do with the surrounding environment. I used that as a way to talk about different environmental positions. Nuclear power is supposed to be clean energy, but how clean is it? And does being clean in terms of relating to the environment mean picking up trash from the beach, or does it mean this thing called “clean energy,” which has turned out to be toxic and something that produces waste byproducts that never break down? Is there anything that’s really clean? Maybe dirt is good. The experience of living in a collective household made me realize that there was no right or wrong answer. We never could get to that; we always had to allow for these differences and differences in positions. We were very interested in the problems that came from that. I was annoyed by it at times too, of course, but I wanted to see how it might work out to try that approach with the landscape. With Tit for Twat, I am dealing with more historical space issues that have to do with ideas about a creation narrative of loss. In the story of Madam and Eve, rather than a fall from grace, the increase of knowledge that my characters gain means that they have more things to think about and more tools for understanding the scope of history and its complications. In the end of that narrative, when they have done all of their time traveling and their touring from museums, to gardens, to linguistic laboratories, and they achieve an understanding about what has happened since they initiated this whole landscape of people, they return to the garden and have a feast and a fashion show. It’s like they have plenty. They are not restricted, and they haven’t fallen from grace, but they are producing their own narrative as they go along. The piece moves it away from an idea of good and evil to an idea about where we are positioned. That necessarily makes it more political because you have to think about where you are in that sense. CL: You mentioned in an email earlier that J.B. Jackson is an all-time favorite of yours. He investigates the vernacular aspect of landscapes, but he also tries to take on another perspective, as when he investigates the military landscape, for instance. And then sometimes, I would get confused and think: but isn’t that now really random, if one can have any possible perspective? And that’s why I think that it’s really an important thing to say that you have to figure out what your position is. How does his way of looking at the world or at landscapes influence you, or how does it relate to your work? KB: Maybe this is a good time for me to talk about my research and how it informs my teaching. When organizing my first class on landscape, I looked to J.B. Jackson and to Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown because in the late 1960s and through the 70s they started looking at what exists in the space around them and figuring that this should be the subject of research and scholarly investigation rather than turning towards ideals of architecture or landscape and then comparing what is to those. They said that we could develop theory about material culture by letting it teach us about space, and this turned everything upside down into thinking about how structures exist in space. And I think it’s really wonderful the way J.B. Jackson expands geographical studies into having to do with the road and the architecture that is established next to the road, thinking about the road as something that should have geographical theory and description applied to it. It opens up the questions of what geography is, and it no longer separates geography into the natural and the built. Rather it acknowledges that it’s all built. I like the directional turn of looking at the “vernacular” because it really starts to think about how we use space, how we construct space, and how we bring meaning to those spaces. CL: In your class syllabus, you include a lecture about Paradise, and then in the following lecture about the Californian landscape, and then about wilderness. Maybe you can talk about the inter- relationship of these three very different concepts of nature and landscapes. KB: I started teaching a landscape class, which looked at landscape and photography, the history of landscape and painting, and land art. It was a one-semester class, and the way we teach classes at CalArts, we teach topics and ideas and not techniques. So it’s a kind of obvious genre, land- scape. And it’s something that I was clearly interested in in my own work. Later, I also taught another class called Gender Geographies about gender and space. I was thinking through issues in 1970s and 80s feminist theory that have been used to discuss artwork and were often about the body, the self, and the female body. But for me, the discussion felt only halfway there in terms of what I was interested in. There is always a relationship between figure and ground when you are talking about painting or an object. The object or the representation of a person doesn’t exist without some kind of context. So in thinking through a figure-ground relationship, then it became important for me to look at space and how the space gets constructed around the subject. I started looking at architectural theory and geography texts. I was looking through what feminist theorists had done in those fields and that was a way for me to start constructing these ideas for the Gender Geographies class. In connection to research for Tit for Twat, I teach a graduate seminar called The Origin and Copies and Strange Creations. That’s a way for me to talk about photography as an object that produces multiples and its status as an art object and gave me an opportunity to talk about notions of author- ship and genius. We read classic texts like Roland Barthes’ “Death of the Author,” Foucault’s “What Is an Author?”, Linda Nochlin’s “Why Have There Been No Great Wom- en Artists?”, and Rosalind Krauss’ “The Originality of the Avant-Garde.” Then we make the link to Creationism, Darwinism, and other searches for “roots” that produce social rationales for power hierarchies that have to do with race, gender, etc., or propose systems whose logic is based on a particular point of origin. When I returned to teaching a landscape class after these other classes, I decided to break it into a sequence of two, one class called The Wilderness and a second class called The Garden. I then began to look at the histories of the concepts of the wilderness and the garden and where they come together, as ideas in art, as well as in theory. In Europe, there was this idea that maybe the Garden of Eden was located in America, that it was an actual place and that they might be able to find it. And then, historically, what happens is that the landscape painters in the East Coast in the 1700s celebrate this idea of this majestic, unmapped, transcendent nature in their paintings. As the U.S. justified its greed for land through the idea of Manifest Destiny and led the great exploratory trips to the West, and as California was overtaken by mining interests and gold fever, they came upon these amazing and very grandiose landscapes, like Yosemite and Yellowstone. The Western landscape looked very much like the bubbling cauldrons of hell or the mists of some biblical narrative space, and they decided that they needed to protect it with a national park system. But all of the language around this is about Eden and the garden. At this point, the wilderness becomes the garden, the wilderness as the first gar- den, as God’s garden. All this kind of transcendentalist theory that Thoreau develops in Walden gets used in the language to justify saving the wilder- ness as the preservation of the world. At this point, the wilderness is not a threat; it’s thought to be/it transforms into God’s garden. CL: Some of your landscape projects are made up of a series of single images like Burned… or the recent work you have just exhibited in Vienna, The Last Time I Saw You. How do these works relate to the more explicitly narrative works? KB: The first time I did a project that was about land- scape that didn’t have characters in the foreground was after the 1997 fire in Griffith Park in Los Angeles. There is a narrative implicit after a fire because there is the return of vegetation or regrowth, right? For me, that work is a shift in direction to make a series of single images, rather than making a narrative with a landscape background. There are forty-five images in this sequence, and they are shown in different combinations. The narrative is not always available, except if you see something that has partially burned vegetation in it or some regrowth, then you get the idea of time, that something happened and something else has happened afterward. There is a specific sequence to the portfolio of the images. I photographed some locations at different stages of regrowth, and they exist as internal sequences. And then in the portfolio, I break that pattern to make clear other particular visual concerns, like the dense vegetation that provides a screen through which you see the horizon, or the presence of mound shapes that I have photographed. I started photographing in Griffith Park in order to understand a landscape that was so unfamiliar to me because it was so different from where I grew up. After the fire, the hillsides were just smoking ground, and I could completely see what the land looked like without any vegetation on it. As everything started growing again, I could see the growth with the underlying structure. I made the images with my field 4X camera, so I was working slowly with a tripod and composing the images through ground glass with a dark cloth over my head. This means that I was looking at the landscape backwards and upside down; I had to abstract my understanding of the space. Last August, I was visiting my father, who at 99 had moved into an assisted living complex near Portland, Oregon. I had been thinking about the central motifs of German Romanticism in photographs after my Wilderness class in the fall and decided to take the time to visit some of Oregon’s most famous waterfalls. This was also particularly because in May, I had visited Triberg Falls in the Black Forest as a follow-up to our class discussions about the “sublime” and its representations. Anyway, even though they are impressive, in my mind they seemed small by comparison to what I remembered about the waterfalls along the Columbia River Highway. During a break in my visit to my father’s new home, I took my field camera and tripod and spent some time taking photos of some of the most touristy sites in Oregon. My father died just before Christmas, and this visit was the last time I saw him. This is a small body of work, seven large-scale photographs of four of the waterfalls, and I call it The Last Time I Saw You, a literal title about my father but perhaps more generally about the flow of loss and change that comes with death and life. The Images are embodied and sexual, which also has to do with life force and the loss of my last surviving parent. I had never thought about making landscapes of such touristy sites before, but I also feel that I have not seriously looked at that landscape before and wanted to consider the problems of making such photos. I think the reason why I make work ultimately is because I don’t understand something, and it’s a way for me to think through the relations either of the characters to the space, or the characters to the narrative or the space, and the components of the space and how they exist in a panoramic sense from left to right and also in a sense of depth from front to back. So it’s really research into my own understanding of something, how I can understand something. And as an attitude of approaching it, I like to stay a little bit empty-headed. In other words, I try to not decide what it is I am looking at before I get there but let that be revealed through the process of making the images. It’s a way of coming to an understanding.

[1] This interview was originally published in Landscape, Volume 2, Summer/Autumn 2012. |