Eileen Myles and JD Samson in Conversation

|

[Transcript edited for clarity, MW] Martabel Wasserman: I was very excited and anxious preparing for this conversation so I decided to email one of my teachers from college, Helen Molesworth, who introduced me to Eileen’s work, to ask for question ideas. To start it off light, I am going to pose to you her response to my request: how does it feel to be such a rock star? Eileen Myles: Rock star is the new poet I think. It used to be if you did anything good, you were a poet, like the poet of rock and roll. Now you are the rock star. For me it’s like being a poet of a poet. Its kind of great, like being Saturn with an extra ring. It’s a new abstraction, a glamorous abstraction. I always wanted to be in a band but I could never figure it out. When I was much younger I thought it was a great idea but just knew I was too much of a fuck up to keep it going. A poem I could keep going. Its kind of great I never I had to become a musician. I am dying to hear JD. JD Samson: I should hold a mirror up because I feel like the exact opposite of what you just said. When I hear “how does it feel to be such a rock star?” I am like ew, rock star, how terrible. I wish you asked, “How does it feel it to be such an incredible poet?” The grass is always greener. EM: That’s great. JD: Rock stardom is really weird 2012. I miss my college days when I was would sit in a room for 10 hours, uninterrupted by the Internet or phone calls, making extreme art. MW: I had a really short but important period where I had that uninterrupted time without the Internet to make art. Maybe a year. EM: I had it in this apartment! Part of what I love about this apartment is that it reminds me of when I just had a telephone and often times it was turned off. JD: That’s really funny because I was just thinking about that when I was watching the Cecilia Dougherty video It’s a video that is a portrait of you through your poetry. EM: Yeah, with my pit bull. JD: I remember thinking this is from another time! I remember you were talking on the phone and thinking oh my god it’s not even a cell phone! EM: (laughs) MW: Speaking of this apartment, I wanted to start by anchoring my questions about the political in local. New York is a significant trope for both of you. What is your relationship with the city right now? EM: My relationship to the city is a little fractured at the moment because I am planning on being in and out of for a period of time. A friend of mine is staying at the apartment, I am just back so we could have this conversation. My life has been increasingly like this for the past few years. Yet my love for the city has increased too. I keep feeling like it’s my favorite place in the world. I am always falling in love with other places, but there is something entrenched about New York. That’s its so full of people and both beautiful and sort of hopeless. I have to say one of my favorite things is the subway. I love the New York City subway. It’s this masterful work of art and collision of all these lives. And you know it’s a certain class, not everyone rides the subway. It’s this beautiful sculpture that is moving through a lot of the classes that are in New York and absolutely not some of the classes. I feel very alive when I am there. It actually makes me want to write a lot. I think New York is weirdly hot and continues to be. It’s like a beautiful mess. There is always a discussion, but I think its really peaking at the moment, about whether New York can come back because it is so much a city for the wealthy. I just had lunch with a guy who is a poet and he has to work so much just to be here. That’s monstrous to me. It’s all of our problem to figure out how to have this place be vital when the need for money and space and privacy and community is so hard won. But it weirdly keeps attracting people. That problem is part of our politic. That’s always the problem, how to be an artist in this place, whatever that place is. New York keeps being the beginning and the latest version of that problem for me. JD: I can echo a lot of those feelings, especially about being out of town a lot. Touring and traveling for performances has both reignited my love for New York but also damaged it in a way. I was actually reading this Henry Rollin’s letter to the public today about traveling, which was asking kids to travel and see the world so that they can come back with a totally different understanding of the government and of everyone and thing around you. In this way, traveling really makes me long to be somewhere else other than New York. I see the rich surviving the poor struggling here. It’s very difficult. It’s been difficult for me to survive doing my art here. So for the past couple years it’s been a question whether I should leave or stay. Trying to reignite the scene here has been frustrating but also exciting, particularly with the Occupy Wall Street movement. I’ve gained much more of a connection to the city politically and with my community. A community of everyone, literally the 99%. Recently my band played for the May Day festivities It was really incredible to play on Wall Street. Doing all the interviews and press around it really solidified this being my home. MW: It’s interesting that you both brought up traveling because its connection I see between your work that I wanted to ask you about. I love how both of you are taking on the trope of reimaging the American landscape in your own ways, through dystopic and utopic languages. I love JD Samson’s Lesbian Utopia project . I was recently reading Snowflake/ different streets and was really relating to your descriptions of moving through different landscapes, particularly resonate for me right now living in Southern California were the poems that referenced driving there. EM: I guess traveling is my favorite thing. I think I was brought up to be that way. I lived in one house in Arlington, Massachusetts from childhood up until age 21. My parent’s fantasy was sadly focused on retirement I think. My dad was a World War II guy who only traveled during the war and saw Europe because of the war. It was clearly what he was most excited about. My parent’s fantasy was that when they were older they would get a trailer and travel around the country. My dad died in his 40s and they never did that. I think that weirdly that one thing embedded in the dream of who we were. It’s not so much that we had privilege, but that we could travel, and travel was the good life. Travel was desirable. It was built into me that if I could grow up and could be an artist that traveled than I would have succeeded. I travel too much sometimes. Weirdly there is a part of me that is incessantly chuckling that I am having this thing I imagined and dreamed of and that I am seeing the world that way. Movement stirs me as an artist so it’s kind of the best thing. The place you come back to is very important if you travel a lot and New York continues to be an amazing place to come back to. I am always glad to be back. It’s a great port. MW: JD what is the tattoo on your arm? JD: It’s a mini van. I also have an RV. MW: Can you talk about that? JD: Yeah it’s funny; I grew up in the same house my whole life too. We would take road trips a lot and it was always a peaceful thing for me. We never talked in the car; we would just drive for like 10 hours a day. It was this moment of solitude. All of a sudden I fell into being in a touring band where this similar routine came into my life. Waking up, getting into the car, and then silence. Always in the states. It was always this American thing. It is weird because it’s a part of me that’s kind of into the United States, in that particular way. I love how there is so much vastness and beauty and you can look out and say the world is over populated but I don’t see a person for miles and miles. So that was a big part of my childhood and touring was just this incredible movement in the same way Eileen mentioned. When I did the Lesbian Utopia trip that concept was to continue to do that and see how this movement as a community could mirror the feelings of being on tour. Being stuck in a small space together, as you are in a community, and moving through time and space together with those people. And not being able to really choose who those people are, it is what it is. The trip was awesome because in the end the lesbian utopia was inside of the RV. Whatever we saw, we saw it together. We had troubles and fears and difficulties as communities do, but it was really awesome. I never really wanted to travel. I didn’t travel outside of the US until the first Le Tigre tour. The first time I went to the UK was the fall of 2000 and that was the first time I left the country. Now I’ve been to China, Japan, Vietnam, all of these places I never thought I would go. But I am a crazy practical thinker that’s thinking I would never spend all this money just to travel. It’s all just coming to me as a gift. MW: I wanted to ask you both about the legacy of the AIDS crisis in your work as queer artists and activists. EM: I am a lot of things but I am a poet primarily and the poetry world is a very particular place. Often I am just the “lesbian” in it. Its not that there aren’t gay people there but it’s parsed in all these different ways. One of the things that I feel I am compelled to do consistently is remind people. Helen [Molesworth’s] show about ACT UP was so important in that way; to have the opportunity to think hard about what the crisis looked like, what the world looked like at the time, how they have changed, who we lost. The peculiarity of the mourning was so intense. Like in the poetry world, I remember suddenly realizing at Joe Brainard’s memorial, which was huge, that for a lot of people this was the first memorial they went to for someone who died of AIDS. People were talking about who he got AIDS from. I was like, “what the fuck?” Conversations we had been having about AIDS for so long people hadn’t even begun to have. Even today. I am going to a conference in Maine called “Poetry in the 80s,” and its very intense because there is a way of talking about poetry at that time excludes it. What survived, its that thing about history, what survived was not that. What survived in the poetry world was the world that wasn’t afflicted. There are whole schools of poetry with right minded, smart people who know about AIDS and lost some people but it still wasn’t there absolute set of friends, and it was mine. So I feel like so much of my work as a poet is to keep thinking of different and new ways to bring that up. To remind us that the culture we have is strained through this incredible loss and that loss is part of what is going on all the time. It’s the same as homosexuality. Like the avant-garde of a certain generation was in the closet. The whole code of the avant-garde was silence. Like John Cage. They didn’t talk about being queer, they just were queer. But that led to a funny kind of affect for the next generation of people who just didn’t talk about homosexuality. AIDS has done that again. It’s not front and center. It’s interesting. Interesting is a weird word. MW: It’s a thing. EM: It’s a thing and it’s a real thing and how to keep pushing that out into the world is part of what my job as an artist is. It’s kind of a monument that needs to be there. JD: I feel like I am part of the generation that has been totally apathetic. MW: I feel like that too and I am about a decade younger than you. JD: I had a cousin who died of AIDS when I was younger. I remember not really having anything explained to me. I knew he had AIDS and died but that was it. We felt sorry for him. We had other “homosexuals” in the family so we didn’t feel bad that he was gay but that he was sick and that he died but it wasn’t a conversation. When I went to college that was the first time I really had the history of AIDS and ACT UP, as part of my studies. I didn’t have it first hand, especially living in Cleveland. My cousin lived in LA so that was a different world. But I was never faced with it first hand. It became part of this archive of queer history that I was going to pay attention to from then on. I remember Larry Kramer coming to my school and talking and that was very intense. Intense is the best word for it because we suddenly felt apathetic and guilty. MW: I remember that feeling. I did my thesis on ACT UP and at first I felt this overwhelming sense of guilt. It is not a productive emotion. EM: (chuckles) JD: Yeah. MW: It was like I wished I were there. Really unchecked emotional responses. Trying to study that period for a sustained period of time was really interesting because I would get very into in my head, thinking theoretically about it etc., and then something would just knock me out. Something would happen and it wasn’t abstract anymore. I would hear someone talk about it or watch footage and it felt like I was being punched in the gut and I would realize I wasn’t just talking about a period of history. JD: This is kind of separate from that but it’s always hard to study something you weren’t affected by first hand, whatever that means. I think about that when I am writing lyrics even, like am I allowed to touch on this? EM: I feel like there is no one art movement there are many art movements. There is no rock star; there are all these musics. Part of that is the legacy of AIDS. In that it didn’t affect one group, it affected all groups. So what we ended up looking at was how all those groups affect each other and how all those groups are one thing. JD: Which makes so much sense that it’s now coming through OWS. EM: Exactly! A movement that sees we are all connected. That’s the economy. I had a girlfriend who was an eighteenth century scholar and one of things I learned from her was that two things were invented in the 18th century, which was the beginning of modernism. One was the economic sphere and the other one was the aesthetic sphere. These things didn’t exist as separate entities before then. But they are these monstrosities that connect us all. As is a disease. One of the big things people moaned about in the 70s and 80s was that the failure of the left was that we couldn’t work together. Some people’s war wasn’t everybody’s war. Each revolution was sort of about somebody. Even though lots of people ended up getting on the bandwagon, it was always ended up being their problem. Whether it was feminism or civil rights or queer/gay liberation. It was always atomized and now it ain’t. Now we are all in it together and that’s kind of incredible. MW: Okay last topic: I want to talk about the body in both of your work since it seems very central. The name of your last album, “Talk about Body” EM: As I have a cat’s butt in my face. JD: Bodies! MW: How has your thinking about the role of your body in your work changed recently? EM: [To JD] I looked at you and you looked at me. MW: And how does translate in the production of your work vs. the performance of your work? Because you guys both have that back and fourth. JD: That’s funny because I was thinking about asking you about performing your work because I was interested in hearing you talk about it. But should I start first talking about body? The record that we are writing right now is more personal to me than even the last one. For the last record a lot of people in the press were like you didn’t say “I” once in the entire record. EM: Wow. JD: I think I say it once or twice but I thought of it as such a “we” thing. I didn’t even realize but this record is completely “I.” I barely say “we.” MW: That’s interesting given that the political moment of the last record was so different from this one. To go from dreaming about the collective body, now that that has kind of emerged in the public sphere, to anchor it in more in the personal. JD: It’s interesting because if you read the lyrics from the last record they are actually really timely right now. But we happened to write them 2007. I wrote this thing for the Huffington Post last year and it was basically everything I said in the record three years before. People didn’t hear the words on the record the same way they did reading a piece online that was shared on Facebook. I am always interested in the different mediums you can use to put out your ideas. Whether you work in the medium you normally use or a different one or whatever, how things get heard. As I get older I am more interested in the duality of my body, can I pass? Do I want to pass? Is it just because it’s easier to pass? MW: Pass as what? JD: Pass as male. Those questions all come up on this new record. That’s probably what I am thinking about most as I am writing. Our last record was really talking about the name of our band, which is MEN, and talking about who gets to call themselves a man, what is a man, what is gender. EM: I feel like I write the work and my body distributes it. In so many different ways, literally traveling with but also, it’s a word I don’t use, but I want to say intoning it. Even though I am a writer, I feel like a recording artist. What I am writing down is a sequence of sounds. As I have continued to perform I have given myself more permission to perform it, which often means being silent and acknowledging how much music is in the words. By stopping the words and saying there is a timing that I don’t know how to write down, I can only play it and I can only play it if I have an audience. I need the you that comes to hear my work in whatever way. When I do the reading, there are the poems, but also I can’t stop myself even though it alienates certain parts of the poetry world, I have to tell stories about the poems. I want people to know how that happened or what this thing is an emblem of. Weirdly its what makes the whole thing be alive for me. It’s taken me years to admit. There was a time when I was trying to be a performer, like in the 80s when poetry was not considered cool, performance was cool. I started memorizing my texts and trying to be a performer. In the writing the world, it meant you weren’t a real writer, you were a “spoken word artist.” There was a class issue suddenly. Slowly over time I’ve realized I hear this work. I am performer, that’s what I do for a living and that’s how I make my living. In terms of gender and sexuality, it is such a changing, changing thing over time. To be on a plane and have one person offer you a drink and say ma’am and another person offer you a pretzel and say sir. I seem to get more androgynous as I get older. I am female but I feel butch. But I feel like my version of butch. I have a girlfriend who is much younger than me and I get referred to as her mother all the time. We went to the hospital the other day and it was a fucking nightmare. Every health professional that came into the room said, “and so this is mom.” So I realized the politics of mom in a way I never had before because she wasn’t a person. It was just ‘this is mom here.’ I wasn’t being talked to. What do I do with that? I can’t fight it every time it happens, I don’t want to fight it. It’s kind of like a Buddhist thing: how to know what my gender is for me and in my relationship and in my community and not worry about what the world thinks. I have been fighting this one for years, whether it’s being on a bus and some bus driver decides I am a man and I wasn’t ready to be a man in that moment. Come up here sir and I wasn’t ready to be a sir in that moment but the bus is waiting for me to come up. It’s getting weirder as I get older. JD: I pass as a teenage boy. So that’s really hard for me as I get older. I am constantly someone’s son or stealing something or something like that. That’s why it actually matters now. I am 33. I am not 12, I am done being 12. It does make me feel differently about my gender and makes me want to perform my gender differently so that I am not 12. MW: In certain spheres your gender and sexuality are so celebrated. For both of you, it’s actually iconic. But then you’re on a bus. How does that back and fourth play out? EM: Or in photographs! People persistently act out their own gender stuff, or definitely on me, in photographs. If I look too much like a man in that picture, they will find another one on the Internet where I look more like a woman. MW: For interviews? EM: Yeah, if they weren’t looking for a queer. Or they like me being older, I have to be the beautiful older woman and they shoot it in really soft light. They like me being really old because that’s profundity for a woman. JD: Sometimes I do shoots and people ask if they can put mascara on my mustache. It’s like what are you trying to do? They are trying to make more extreme the extremities. EM: Yeah, just by the fact of being different. It’s like being pregnant; people are always touching pregnant women’s bellies. By being different you have somehow given the world permission to tweak, because you aren’t normal. Its really intense learning how to defend that territory, and learning how to fight for it. And when not to fight for it, learning how to pick your battles. JD: As a performer, I feel like my persona is totally different than who I am in real life. I just have to make that separation. My gender presentation isn’t different but I am just more confident and safe when I am on stage. Or doing an interview or whatever because those people know who I am, what I do, how I perform my identity. Whereas if I am walking down the street, I am more afraid. EM: That’s such a good point and so interesting, how safe it feels to be on stage. JD: Michael Jackson did an interview with Oprah where he said, “I am more myself on stage than anywhere else in the world.” I always use that in interviews because I totally agree with that. MW: Do you and your girlfriend address gender issues differently because generational differences? EM: The thing that is everyone is part of the generation and then not. MW: Generation is a funny word. EM: I am enormously grateful to be involved with someone from a generation where everything is very fluid. In a weird way, I feel like I have to explain myself less with her than with anybody. But it’s hard to separate what is love and what is generational. There is a whole queer world in middle America that is not very fluid around gender. We got really harassed on lesbian websites. People were writing pornography in our name. MW: I love the poem you did together. JD: People were criticizing the age difference? EM: People were saying I am predator or that I was old grandpa or grandmother. Or she has to change my diapers and I am shitting pants. And she was clearly sexually abused. JD: These are queer people? EM: We don’t know because it’s the Internet. Vice did a thing on queer power couples a few years ago and there was a picture of us. We didn’t like the picture of us, it was kind of a gross picture, it wasn’t sexy at all. I was sort of shrugging and she looked particularly young. She was like a tall daisy. MW: That’s probably the most circulated picture of you guys. EM: Yeah, first people started saying shit on Vice. Then they shut down the comment board and it went on After Ellen. I guess there weren’t any gay couples of different ages. MW: Which is such a queer thing. EM: But with men, of course it’s totally cool. Men can do anything. With a woman you are a predator. JD: I’ve had annoying Internet shit too. With the Huffington post thing, I was like if I were a man would anyone have written anything? MW: What did people say? JD: Quit your whining. Or don’t be an artist. EM: Because you talked about economic issues. I loved what you said. MW: I did too. JD: I expected there to be something. Its interesting because my girlfriend is only six years younger, which I don’t think of as a big age difference but it is a difference generationally in terms of gender. She thinks much more fluidly about gender expression than I do. I am clearly interested in a fluid gender spectrum and that’s what I am working towards in the community but I am definitely much harder on myself. She is like ‘why do you care if you can see your boobs?’ Which has to do with passing but she is much more comfortable with my gender identity than I am in some ways. And it’s only a six-year age difference. MW: But that is a significant period of time. When I was doing research for this interview I was thinking a lot about how different your press from the Bush Era is from that of the Obama Era. Its crazy to reflect back on because I think its repressed in a lot of ways. EM: With trans for example, its not new as the way or road to talk about these issues but not that long ago it was just butch/femme, top/bottom, and you really had to define it. But trans blew it out of the water. I am saying obvious things. It made the butch category a challenge. MW: JD are you going to Michigan [Women’s Festival] this year? JD: No. I’ve been going since I was 17. I got a ride from a ride board from a feminist bookstore. I went by myself. It was the first thing I did by myself before I went to college. I have a really intense relationship to it that is very separate from any conversation about gender. Its literally going back to this place where I had an extreme coming of age experience. But it’s so very problematic year after year. You can see it now at the festival taking shape as a more visible argument. EM: The gender thing? JD: Yeah, people who are trans coming and people having problems with that. And people wearing shirts and armbands saying what they believe. MW: Its very funny how things change so quickly generationally. I am in grad school and I went to an undergrad LBGTQ organization to talk about a project I was doing. Going around the room introducing yourself everybody is asked to say their preferred gender pronoun. It made me so uncomfortable because I didn’t want to have to identify as a woman, what does that even mean? And then people saying the project I was doing was not radical because it touched on Prop 8, but I was trying to complicate it and connect to immigration, income inequality, etc. They were being very accusatory about how my politics were not “radical” because I wanted to talk about marriage as a question. JD: I went to Sarah Lawrence and we had the same kinds of conversations when I was in college. We were in this bubble of radical politics and it was about this hierarchy of who could be the most radical or most wild. And you’ll see that in different forms your whole life. MW: I believe in radical kindness. JD: Or radical honesty. MW: So one other connection I wanted to bring up was the poster my friend and I did “JD for President” because I got that idea from Eileen running for president in 1992.

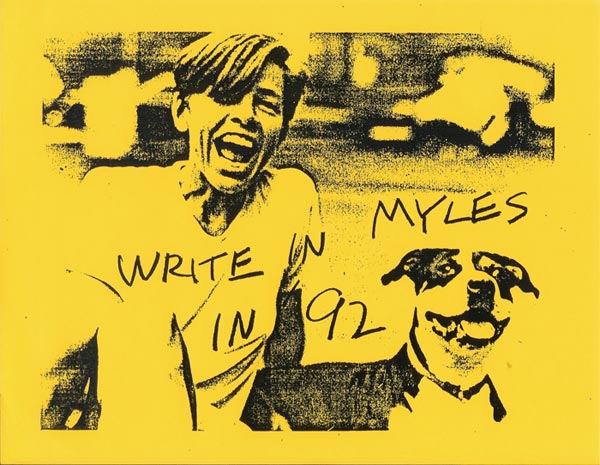

There is this election coming up, a lot of shit going on. What interventions are we going to make? How are you guys thinking about being artists and activists in this moment? Do you think about electoral politics? Are they important? EM: Unfortunately I think it is important. Whether we get Obama or Romney is going to make a big fucking difference. All I can think of, as an artist is that I just want to bring that to every performance I do. Whether it’s the work or what is in between the work that addresses it. To use performance as an occasion to talk about politics, I think that’s a big function of art right now, to bring people together. I think before Occupy that was really clear, the only thing bringing people together were art events. But once you get them there you should do something. Running for president was an incredible experience because it gave me a new sort of permission to be an agent of my own politics. In the sense that if this is my country, if I did live here and I did have this much say over my government, what would I do? It birthed a kind of imagining. Its kind of incredible that I never had the right before, even as a citizen, to take information and to think of that as what I make something out of. By making it be my work, I realized that was my work and would always be my work. What people treated as a cartoon was actually a profound porthole. MW: Starting with Victoria Woodhull, that’s kind of like a lasting cartoon. People thought it was a joke but it still resonates with us like 100 years later. I am bad with dates but something like that. JD: I actually have it written down because I was just going to use it in a song. I was reading this book about all the things you don’t learn in history class and there was a chapter on feminism. It’s so crazy because the book is very square and conservative. I just started writing down all the people’s names in it and was going to make a song with them. It’s a weird cross-section of feminist culture from a mainstream perspective. People always ask me in interviews, if you were president what would you do? I am always like I am not a politician. I might be singing about politics but I am not politician. I never actually thought about what I would do. MW: Have you ever read the Zoe Leonard piece “I want a president.”? EM: Yes I love that. JD: I just reposted that. Someone put it on Facebook the other day, and I was like good timing. My band is trying to go play gay bars in small towns in October. We are going to try to raise money or get grants to try to target small town queers. Small towns, big change tours. That’s what we are hoping to do. EM: I don’t watch Bill Maher. I just watched because John Waters was on. It was awful because it ended with him bashing Occupy for a long time. MW: Jon Stewart does that. The liberal media pundits are always denouncing socialism. JD: I was on tour and I happened to see one episode where they went to Occupy and made fun of everybody. Some liberal show. Rolling Stone just had something about the implosion of Occupy. I was like, “how dare you?” MW: That’s not productive. JD: First of all, they were one of the main press groups at May Day doing a positive report. And the main things they end up writing about were internal struggles. EM: The interface of a large corporate media with a small communal, grassroots cause, or whatever you want to call. Its incredible classism. JD: It’s so clear how capitalism has risen in that case because who owns every one of those major magazines? And don’t think they aren’t in charge of what goes in them. I was just reading an article about the top songs and they are all from the same place and the same guys own them. Nobody has a chance anymore. EM: They were laughing about when will this stop being a camping trip. MW: Or when will the drum circle stop? EM: The bodies are there! That’s really significant that people are sleeping and living there. That’s the politic. JD: Hopefully things will get even wilder as the election approaches. EM: It’s a scary time. JD: I know I was talking to my grandpa who is 90 on the phone. He was going to his social studies class where they talk about current events and he was like, “I don’t know who I am going to vote for.” I was like, “Really? For my lifestyle there is one choice.” “But do you know how many people have died in war since Obama has been president?” For his generation, or at least for him, the most important thing is not being in a war. MW: Which is an important thing. But it’s not going to better under Romney. Okay we are running out of time, lets say something positive! JD: I am excited because we are all going to hit the streets. EM: Yeah the closer it gets to us, the more intense it will be, and the more powerful our voices will be. |