The Politics of Apathy by Christopher J. Lee

|

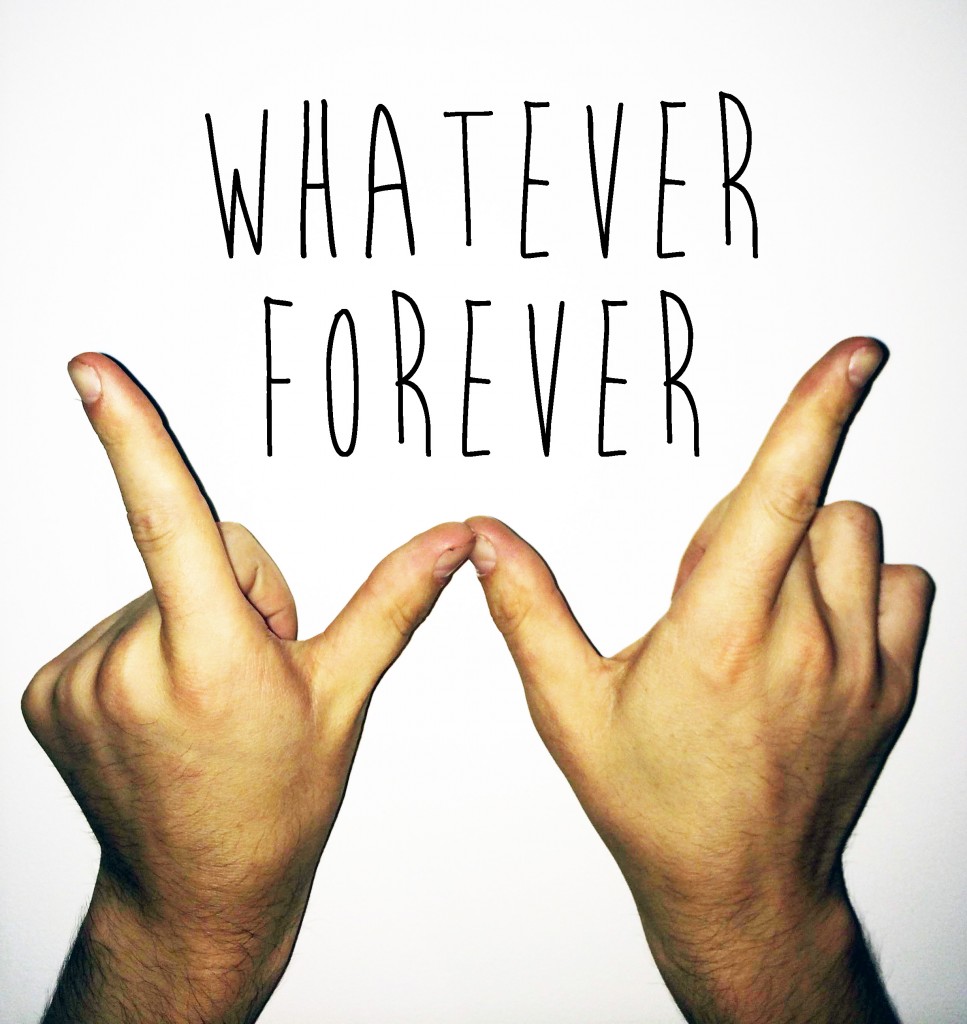

Of the many charges leveled against the so-called millennial generation, there’s none more damning than ‘apathetic.’ Stock photos of bored young people corroborate questionable reporting; millennials evidently spend their time lying in grassy meadows, resting their heads in their hands, and staring off into the distance. This consensus narrative betrays a pathologizing impulse. Disillusioned youth suffer from the diagnostic state of apathy, with such conditions as political detachment, poor health, cyber-addiction, self-indulgence, underemployment, oversleeping, and permanently shrugged shoulders. While ageism provides some explanation for the apathy argument, many of those crying ‘apathy’ are themselves millennials. Nearly every college newspaper has some variation on the anti-apathy screed, with indictments as vague and uniform as their coordinate remedies: get out and vote, serve your community, stand up for what you believe in, make a difference. Care about something, anything, and you’ll find yourself in the graces of a well-ordered society. A few years ago, I stumbled upon a critical insight by way of distraction. Millennials are, after all, expert daydreamers, and my mental detour—classically prompted by an excess of idleness and classically resulting in no commodity value—led me to an ironically productive paradox: I believe in apathy. I care a lot about not caring a lot. And I feel strongly that indifference must mean something, especially if it draws the concerned coverage of media outlets in service of surveillance and regulation. The tone of this piece is intentionally polemical. Advocating apathy aims at disturbing a political imagination singularly rooted in an economy of caring. We’re conditioned by way of symbolic inundation to perceive caring as an active operation: our fists can smash the state, the subaltern can speak, an end to oppression is just in sight. We have to want it hard enough. Start a project, make a Kickstarter, share it on Facebook, signal boost, signal boost, signal boost. There’s no denying the political efficacy of caring because there’s no other way to be political. Representation politics is the prime dominion of caring, a competition of wills and desire for the future, for the nation-state, for our planet and existence. In a political landscape bound by campaigning and lobbying, it’s easy to care, and even easier to exploit caring for economic and cultural gains. Corporations have seized readily on our anti-apathetic tendencies, with catchy slogans designed to attract our concern and thus our capital. Take this slew of corporate mottos: Whole Food’s “Whole People, Whole Planet”; Coca-Cola’s “Coke Cares”; General Mill’s “Show Your Helping Hand.” Generating profit from publicized compassion is an accepted marketing technique, and it’s an effective one. How does one resist a society that demands caring? Is it enough to care more, or about other things, or against things? Is it acceptable, or even significant, to be strategically apathetic? Millennials are depicted as a media-saturated generation—memes in every image, every occasion an opportunity to broadcast social information and data, which in turn are mined for corporate interests and targeted advertising. There’s ample cause, then, to be ambivalent, to temper our best wishes to care about everything and make our opinions known. Apathy matters because it aspires at a positionless position from which to examine the symbols we’re supposed to care about: family/future, nation/empire, value/commodity. Apathy imperils a prevailing socio-economic system that privileges conception, construction, and utility. My claim, thus, is not to the absolute cessation of care, but to a consideration of how care operates as an apparatus for social conditioning. It’s easy to be upset because the world is profoundly upsetting. For those at the margins of our existent structures, for those who have peered into a reality mediated by regimes of power, for those who see systematic problems beyond the scope of personal intervention, caring comes involuntarily and swiftly. Critical theory doesn’t come with a disclaimer, but it should: following exposure, everything will make you angry. A shorthand list of things that I’m supposed to care about: government shutdowns, HBO’s Girls, the concept of ladies’ night, the politics of gluten, the wedding industrial complex, and now, the never-ending saga of Miley Cyrus. What does it mean to be called apathetic? What does it mean for a generation to be systematically dismissed and undervalued for its perceived lack of interest? Subcultures have methods of parsing the words used against them—by way of anticipating, and then subverting belittling epithets (take, for instance, queer). There’s no lack of identifiers to play with vis-a-vis apathy: burnout pride, slacker solidarity. What I’m proposing is an activated indifference, a weaponized apathy that resists, if impossibly, the caring mandate. This incitement to indifference forgoes a fixation on political ubiquity in favor of a curated system of care. The myth of millennialism is hopelessly misguided, undermining a ‘generation’ on the basis of putative social standards, prescribing teleology under the guise of traditional values, decrying media obsession via the production of more media. And yet, apathy itself might have some weight, if only for its strategic necessity. Apathy is political to the extent that it rejects normative political frames, which privilege production and consumption. Sometimes I stay in before I speak out. Sometimes a dance party is an act of resistance. Sometimes I’m an Aries first and everything else second. I’ve taken an interest in apathy because I need to give myself license not to care—to embrace affectlessness and accept the limits of language and investment. Christopher J. Lee is a freeskool instructor in the Department of Whatever, where he’s taught classes on apathy, astrology, and queer theory. He’s an infrequent author of semi-serious poems, some of which appear in local zines. |