The Becoming — Lupe of Mario Montez by Lara Mimosa Montes

|

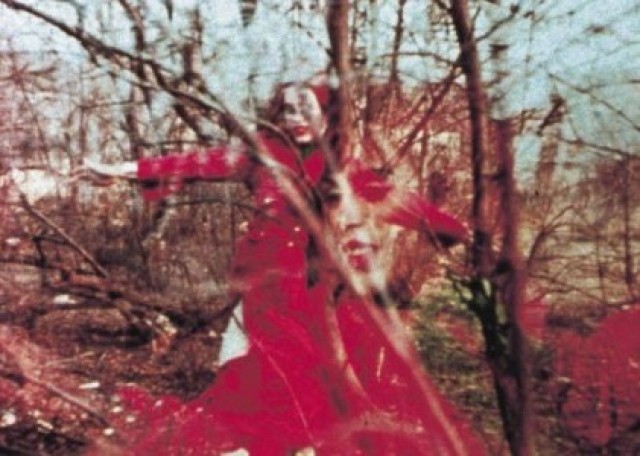

Is it becoming to be a woman? I suppose it depends on how one does it—becomes, that is. It also depends upon what kind of woman one becomes and whether or not such a becoming is becoming: flattering, fitting, befitting. Attractive. In cinema, the close-up shot established a woman’s becoming as contingent upon the size of her (sur)face. By zooming in, the close-up shot could track a woman’s emergence, capturing, for example, that signature smile: pure potential at play, grace, immanence. Such a capture consecrates The Beauty’s having-arrived, to herself and to us. As in Carrie (1976), the nobody becomes-woman, bleeds herself into being, and eventually becomes a hemorrhage of herself—in highschool (or hell), we welcome Sissy Spacek as our new teen queen. Given Laura Mulvey’s claim that “cinema—the cinematic apparatus—is a technology of gender,” it is imperative that we continue well after Carrie to narrate the ways in which the screen brings into being new fantasies, new faces, new fractal, fractured female modes of being. In her book Becoming-Woman (1997), Camilla Griggers observes that the phenomenon of “becoming-woman . . . implies being facialized, undergoing facialization, and having one’s becomings captured by the despotic face of white femininity.” To become a woman is to lose face. But for the actress of color, becoming-on-film may also open up a space for the performer to challenge “redundant” cinematic representations of race. I take José Rodríguez Soltero’s 16mm underground classic The Life, Death, and Assumption of Lupe Vélez (1966) to be an instance where we may consider Mario Montez (of Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures and Andy Warhol’s Mario Banana) as a performer who refuses racially redundant representations by becoming the “Mexican Spitfire” Lupe Vélez. Lupe Vélez, infamously remembered in Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon, was a Mexican actress and performer of 1930’s Hollywood and Broadway notoriety. Vélez, known for her wild Chicana excesses, was also an obvious tabloid favorite. As early as 1929, it was rumored, “Lupe can love five men at the same time, with incredible ease, and love them all for five different reasons.” What a woman! But according to Rosa Linda Fregoso’s essay, “Lupe Vélez: Queen of the B’s,” it was the gossip coupled with the masculinist judgements of Vélez’s public life as a Latina which contributed to the “flapper Azteca’s” disrepute. Fregoso recognizes that although Vélez “provided young women with an alternative model of female behavior and identity,” she was unfortunately also “more often maligned in Latino historiography for perpetuating a negative stereotype of Latina identity.” Her refusal to comply with standards of Latina decency made her something of a scandal. Una sinvergüenza. She was, to her detriment, a woman without shame. At the age of 35, Lupe Vélez, who was four months pregnant, committed suicide by way of a Seconal overdose. As William A. Nericcio writes in homage, “our beloved Santa Vélez . . . some fusion of Calvary and Hollywood, where the Vatican and Tinsel Town merge as our marvelous spitfire, cum martyr, ends her time on the planet.” And so it is here at Lupe Vélez’s death that we arrive backwards at Lupe’s asunción. This asunción, an elevation, can be thought of as her adoption into the Star system where in death, the star becomes what Richard Dyer calls a heavenly body. And yet, in Rodríguez Soltero’s Lupe, there emits, through Mario Montez, the bright light of a distant star. How does the loss of Lupe become transformed in the queer Latin/a imaginary? Or, what becomes of the legend of Lupe Vélez? According to Elizabeth Grosz in her book Volatile Bodies, “Becomings are always specific movements… always a multiplicity, the movement or transformation from one ‘thing’ to another that in no way resembles it. Captain Ahab becomes-whale, Willard becomes-rat, Hans becomes-horse.” In the case of Rodríguez Soltero’s film, Mario Montez becomes-Lupe. The collaboration between the director Rodríguez Soltero and the performer Mario Montez, both Puerto Ricans, envisions a life for Lupe filled with energia. The two lived in the same building on Center Street, near Canal where Mario “regularly combed TV Guide looking for oddities and held late-night film-watching parties” (Suárez, “The Puerto Rican Lower East Side and the Queer Underground”). Like the Kuchar brothers in the Bronx, together, they drew on Hollywood lore in order to create what J. Hoberman would describe as “super-saturated Kodachrome II thrift-shop glamour.” Ronald Gregg tells us in his forthcoming book Birds of Paradise: Costume as Cinematic Spectacle: “The centerpiece of [Mario’s] living room was the television, his entrée to Hollywood, which he decorated by placing a pearl necklace around the screen.” Certainly, decorating the TV with a pearl necklace is a queer gesture; it suggests that for Mario, one learns how to become a woman by tending to one’s screen. As Montez once said, “I learned my acting basically from watching old movies.” It was also no secret that Mario’s exotic tropiholliwood tastes were cultivated in tandem with Jack Smith’s.[i] In the topos of Atlantis, or Loisada, to be a woman-on-screen was to be a flaming creature—a spitfire—a spectacle. In Oscar Montero’s article, “Lupe: las visiones de Rodríguez Soltero,” Montero describes the spectacle of Mario’s becoming-Lupe as her becoming Salomé adorned in pearls and gold– “una mujer intocable, letal, tan bella y famosa como la Monroe, tan fabulosa como la Taylor, pero inalcanzable, como las estrellas del cine mudo.” In the Salomé scene, Mario invokes the Atlantis of Jack Smith where through Mario, Lupe becomes a heavenly body gyrating her way through the cinematic centuries in the celestial company of Marilyn Monroe and Liz Taylor. In contrast to Andy Warhol’s Lupe (1965), which stars the white Edie Sedgewick as Lupe, I suspect the ethno-identification between Montez and Rodríguez Soltero produces a very different kind of film—one which celebrates the vivacity and color of Lupe Vélez’s life. As Juan Antonio Suárez observes, “Rodríguez Soltero takes some liberties with the facts and produces a color-saturated, gorgeous dime-store baroque that tells of Lupe’s rise from whoredom to stardom, her fall into fractured romance and suicide, and her ascension into the spirit world.” Interestingly, the film reflects a mezcla of Hispanic references, few of which are Puerto Rican. For example, “Gracias,” the opening song of Lupe sung by the Mexican singer Javier Solís; as Arnaldo Cruz Malavé observes, the song, which plays against the black screen, establishes the aura of appreciation and homage. One may even recall while listening to Solís’s voice the pageant song, “There She Is, Miss America.” To then see Mario Montez, who is also a queer reincarnation of the Dominican-born star of Cobra Woman Maria Montez, at his most beautiful playing Lupe, one shudders. There he is. Miss America! Warhol’s Lupe is far more recognizable as a portrait of Edie Sedgewick and her deterioration than Lupe Vélez’s, even though narratively-speaking, it presents a more accurate version of events. Rodríguez Soltero’s Lupe on the other hand eschews narrative fidelity in order to simulate the turbulent, ecstatic becoming that was Vélez’s life. As a result, the ‘ending’ that Lupe gets courtesy of Mario Montez and Rodríguez Soltero is far more generous than whatever can be said of the ending given to Edie. As Lupe, Mario moves into the saintly space occupied by only the most marred. Suddenly, like Divine out of Genet’s Lady of the Flowers, Lupe, through the eyes of her admirers turns into a thing immaculate: part-ether, part-image, a red blur spinning away to Martha Reeves & The Vandella’s song “I’m Ready for Love.” In this ecstatic image we can appreciate why Lupe as Edie cannot become-Lupe is because Edie and Andy’s whiteness, queer as it is, just isn’t becoming, befitting, appropriate. No, a white Lupe won’t work. It won’t work because as Frances Negrón-Muntaner wrote (in reply to Douglas Crimp’s “Mario Montez, For Shame”): “shame is the stuff our ethno-nationality continues to be made of.” The shame Negrón-Muntaner refers to in this instance belongs historically to Puerto Ricans. Negrón-Muntaner (and Lawrence La Fountain-Stokes, among others) is taking Douglas Crimp and Andy Warhol to task for skirting the issue of race. Keeping this in mind, I would advocate finally that it is important to contextualize the shame of certain screen bodies while attending to the specifities of their emergence. It is also important that while commenting upon these bodies, we as scholars and performers do not elide or avoid the nature of our identifications as well as our disidentifications, as demonstrated in José Esteban Muñoz’s invaluable book Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. What would it mean for me, a queer Latina performer based in New York, to discover by chance that Mario Montez was not just Jack Smith’s or Andy Warhol’s superstar, but also the lesser known José Rodríguez Soltero’s? And what would it mean to identify with Mario-as-Lupe’s joy, the joy of becoming not just a woman, but that thing that Beauvoir said didn’t exist—essence, but an essence as escupe-fuego. Spit fire. [i] The term “tropiholliwood” comes from Hélio Oiticica’s “MARIO MONTEZ, TROPICAMP,” http://www.afterall.org/journal/issue.28/mario-montez-tropicamp **Thank you to Beth Greenacre at Rokeby Gallery for kindly calling to my attention Oiticica’s piece.  |