On Roads and On Roadmaps by Flora Kao

|

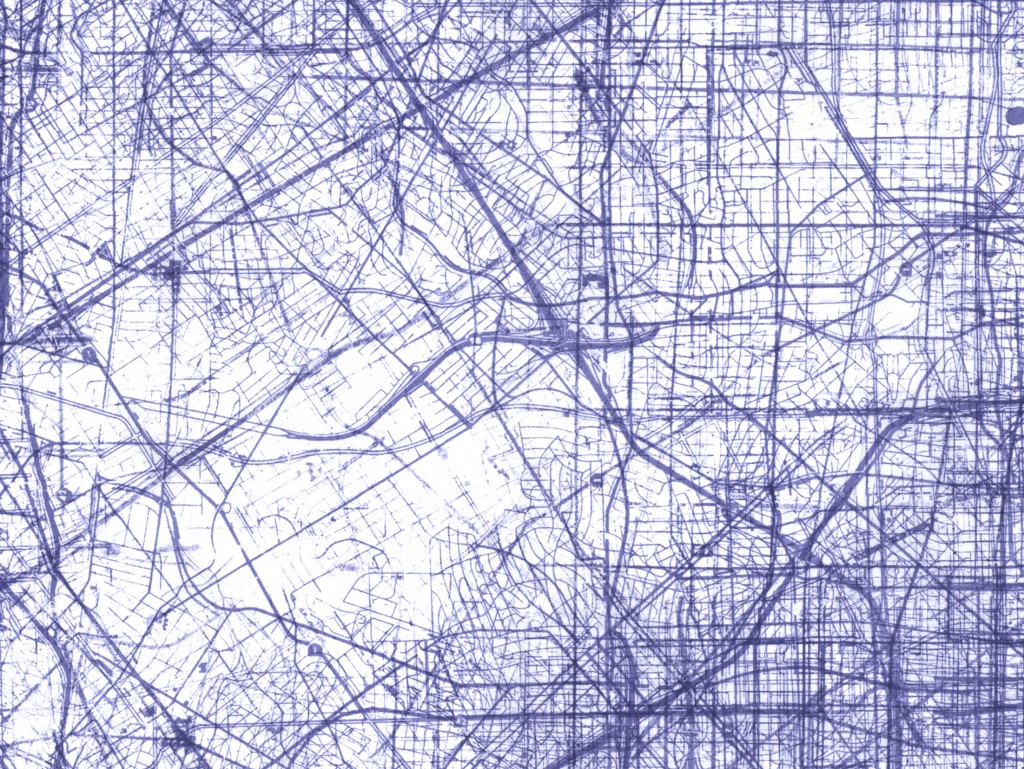

Flora Kao, Lines of Desire, 2008 Acrylic on vellum 7.5 x 10.5 feet [Detail] Referencing the blueprint as a locus of dreams, Lines of Desire is made of hundreds of overlays of the LA street-grid on vellum. Upon approach, its delicate atmospherics morph into a tangled sprawl of streets and vein ON ROADS I awake to a strange symphony of sound. The dissonant beeps of reversing machinery, an endless series of syncopated honks, the creaking revolution of caterpillar tracks, and the rumble of idling trucks. My house shudders in response. I open my door to a cloud of acrid dust. The right half of the road has been reduced to a trench, ten feet wide and one foot deep. Asphalt removed, the ground is a confusion of layered treadmarks. A curious waltz evolves as an asphalt milling machine churns chunks of road for recycling, spewing debris into waiting dump trucks. Two honks forward, one honk back. A rudimentary dance figure progresses up the street. Three honks, full. Next truck. Asphaltum (or tar) has been used since antiquity as a binder, mortar, and caulk. Developed in the nineteenth century, asphalt pavement is now synonymous with urban development. Roads devour eight-five percent of American asphalt, with the remainder used in roofing products.[i] Los Angeles, in particular, is defined by its relationship with asphalt. The tar seeps that dot Los Angeles are surface reminders of the eleven oil fields that lie beneath the city. The La Brea Tar Pits trapped animals over tens of thousands of years. Set aside specifically for public use, asphaltum from Rancho La Brea was used for fuel and waterproofing by the eighteenth century settlers of El Pueblo de Nuestra Senora la Reina de Los Angeles. Having located an Echo Park parcel bubbling with tar, Edward Doheny drilled the city’s first oil well in 1892, spawning a massive wave of oil and real estate speculation. By 1925, the Los Angeles Basin produced nearly half of the world’s oil. Today, the basin’s forty oil fields extract twenty-eight million barrels each year, a fifth of its 1969 peak. [ii] In Los Angeles proper, eleven oil fields stretch from the 405 freeway to downtown. In this dense urban environment, oil derricks are camouflaged in mobile, painted towers and pumpjacks hide behind heavily landscaped, windowless facades. Obscured from public view, oil wells dot sites from Beverly Hills High School to the Beverly Center shopping complex. Golf courses like Rancho Park and Hillcrest are perfect screens for oil extraction. Los Angeles’ thick and low grade crude oil is ideal for use in asphalt.[iii] As the West Coast’s largest manufacturing center and busiest port, the Los Angeles economy revolves around the automobile and its requisite roads. Southern California’s balmy climate favored the early adoption of Henry Ford’s open air Model T. By 1925, Los Angeles supported more than one car per two residents, surpassing the rest of the nation by thirty years.[iv] The automobile accelerated development of previously inaccessible agricultural land, catalyzing a new wave of real estate speculation. Aggressive freeway construction fueled suburban sprawl, with thousands of citrus trees bulldozed daily throughout the 1950s.[v] By 1970, over a third of Los Angeles County’s surface area was designated for vehicular use.[vi] Today, gridirons of roads stretch deep into the surrounding desert. Spanning nearly 500 square miles, Los Angeles is covered with 6,500 miles of public roadways and 800 miles of alleyways.[vii] Maintaining these roads consume 600,000 tons of asphalt each year.

[i] Los Angeles’s eleven oil fields produce two million barrels annually. Center for Land Use Interpretation. “Bus Tour of Urban Crude.” Newsletter: The Lay of the Land. Spring 2010. <http://www.clui.org/newsletter/spring-2010/bus-tour-urban-crude>. Cited 16 May 2011. [ii] For example, non-golf holes at the Rancho Park and Hillcrest golf courses produce nearly 60,000 barrels each year. Center for Land Use Interpretation. [iii] Center For Land Use Interpretation. [iv] Davis, Mike. City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles. New York: Verso, 2006. 118. [v] By 1925, the city of Los Angeles had parceled out enough land for seven million people, fifty years before the actual demographics would match the speculated real estate need. This resulted in 600,000 empty subdivided lots.

[vi] Davis, Mike. “How Eden Lost Its Garden: A Political History of the Los Angeles Landscape.” The City: Los Angeles and Urban Theory at the End of the Twentieth Century. Ed. Edward W. Soja and Allen J. Scott. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996. 160-185. [vii] City of Los Angeles Street Maintenance Division. Updated 2011. <http://bss.lacity.org/StreetMaintenance/index.htm.>. Cited 16 May 2011.

ON ROADMAPS Roads at the turn of the twentieth century were often unmarked, dirt affairs. These rutted roads supported travel by horse and buggy or by foot but were ill-suited for the novel inventions of the bicycle and automobile. Developed in 1885, the safety bicycle whetted the American appetite for independent travel and exploration. Affordable and low-maintenance, the bicycle allowed people to travel moderate distances at their leisure. Bicycling highlighted the need for better roads and maps by which to navigate the landscape. Prior to this point, published maps emphasized geopolitical features like state lines and rivers in relation to cities and railroad nodes. As millions of Americans bought bicycles, cycling associations like the League of American Wheelmen began charting detailed maps of local topography and streets. Henry Ford’s Model T launched America’s embrace of the automobile. The number of car owners grew exponentially, from eight thousand in 1900 to a million in 1912 and over ten million by 1920.[i] Freed from the prescriptive routes and timetables of railroads, Americans embraced the idea of spontaneous adventure in the countryside. Responding to the growing demand for roadmaps, printers overlaid automobile roads onto existing railroad and bicycle maps, but the lack of street names and labels left much to be desired. To find their way, motorists were forced to consult narrative guidebooks that listed the wayside landmarks by which to navigate. Automobile associations collated thick guidebooks detailing directions, road conditions, and repair stations. Strip maps indicated the mileage between landmarks like Blacksmith Shop and Shanty along the most efficient route from point A to B. Other guides like the 350 page Rand-McNally Chicago to New York Photo-Auto Guide of 1909 offered visual cues for navigation. Arrows and captions framed photographs of each intersection to better indicate the turns required for successful travel. To address the general lack of signage, mapmakers literally took to the roads to chart 50,000 miles. Driving across the country, employees staked routes with colored highway logos to mark the “complete, comprehensive system of blazed trails traversing all sections of the United States” detailed in the Rand-McNally 1920s Auto Trails Maps series.[ii] Roadside vendors joined forces to lure tourists to their doors, marking and mapping routes with romantic names like Ben Hur Highway, Cornhusker Highway, Magnolia Route, and Lone Star Trail. Realizing the vast marketing potential of a well-designed roadmap, tire and oil companies began giving away millions of touring maps, vying for customer loyalty with increasingly beautiful illustrations. The enthusiastic, grassroots efforts of disparate cartographers and auto trail associations resulted in an accumulating chaos of roadside signage. By the 1920s, state governments had realized the need for systematic, numbered highway systems. In 1926, the federal government finally instituted a labeling system for a nationwide highway grid, with odd numbered north-south highways and even numbered east-west highways. Towns and trail associations lobbied aggressively for inclusion in the new highway system, even while bemoaning the loss of the auto trails’ evocative names. The New York Times wrote “the traveler may shed tears as he drives the Lincoln Highway or dream dreams as he speeds over the Jefferson Highway, but how can he get a ‘kick’ out of 46, 55 or 33 or 21?”[iii] Inspired by Germany’s high-speed autobahns, President Eisenhower initiated construction of the US Interstate Highway System in 1955. These limited access super-highways dramatically changed the American experience of landscape. The straight four or six lane highway shortened the cross-country drive to just a few days. The road trip’s focus shifted from serendipitous exploration to finding the fastest route to one’s destination. Dramatically simplifying travel, the interstate highway system eliminated the need for thorough, illustrated maps. With travelers speeding past sparsely scattered off-ramps, contemporary roadmaps provide drivers with a minimum of visual information, echoing the bland efficiency of the freeway.

[i] Yorke, Douglas, Mark Margolis, and Eric Baker. Hitting the Road: The Art of the American Road Map. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1996. 14. [ii] Yorke, et al. 40. [iii] Quoted in McNichol, Dan. The Roads that Built America: The Incredible Story of the U.S. Interstate System. New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 2006.

|