Office Hours with Jack Halberstam

|

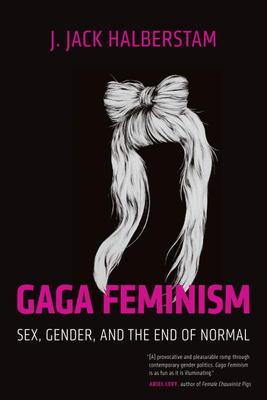

Martabel: How would you describe your practice? Jack: Practice is a tricky word. My practice is associated with public intellectual labor, with being out in the world, and taking some of the work I do in the context of the university to other places. I often give talks in non-academic contexts and try to create public intellectual zones where there is an exchange going on — less like people coming out of the Ivory Tower and dispensing wisdom, and more producing the conditions from which knowledge can happen in a broad based way. MW: On a daily basis, what does that look like? Do you consume a lot of popular culture? In the broadest sense, how do you collect material? Do you read certain blogs, watch a lot of television, etc.? JH: I read a couple of newspapers everyday. I watch some TV. I get very obsessed with series. I have watched all of The Wire, all of Mad Men. There are certain series that I think capture their moment very well, like The Sopranos. I go to tons of movies. One of the things that is really happening here in LA is the art scene, so I try to be out and about in that. I think all of those things are part of a practice, so that’s a good point. MW: You all ready touched on this when you mentioned creating new zones for conversation, but I wanted to ask you to talk more about how and why choose the platforms you engage with — for example, blogging — that extend beyond what we think of as a traditional academic practice. JH: One of the things I think is important in general is to keep up with the modes of technology available in any given moment. In my career there have been many different platforms available. When I began my career back in the early 90s, we were just making the transition from typewriters to computers, from linear handwritten notes to cut and paste productions in Word Processing. I think it’s important not to miss transformations in technology because the platform changes the product. As a grad student I used to do film reviews and I really liked the immediacy of that: going to see a film, writing a review that you think will be engaging and makes a point, publishing it that week in the local paper. The blog works that way for me. People are less apt to pick up a local newspaper or free weekly but they are more apt to look at certain blogs religiously. MW: Do you feel any resistance within the academy when you engage in that type of production? JH: Actually, no. In the university, at least the administrators know it’s important for their faculty to operate on multiple levels at the same time. There are resistances within conventional disciplinary contexts, for example someone in an English department might not see a blog as good as an essay in a recognizable journal. I don’t feel like everything I write has to count academically, some of it can just count in the world. MW: I wanted to talk to you a bit about how we can apply queer temporality as a tool for understanding our current moment. We just put out our first issue a month ago and it seems like since then we have taken many steps backwards. In my last letter from the editor I wrote about how Obama nixed the Keystone XL pipeline, and now he is going ahead with it. We have seen a revved up war on women, the murder of Travyon Martin — which shows us again the racist fabric our country was crafted from — the list goes on. I was wondering how if at all we could think of queer time as a way to understand this inertia both theoretically and as a tactic to resist it. JH: One of the first things in any kind of theoretical programs you learn in a university is that the narrative of progress is wildly fantastical. History never does move forward in a straight line, advancing the cause of humanity at every step. If you look back at the 20th century, despite huge advances in industry, technology, literacy, health, food ecologies etc., it was still the time in which these massive genocides occurred. One aspect of theoretical inquiry has focused on the fact that the Holocaust happened in one of the most developed countries in Europe, to one of the supposed most enlightened groups of people. Progress sometimes means harsher punishment for those who are seen as outside a certain dominant structure. That’s one thing I want to say immediately, that progress is always a fiction. The second thing is that while we are out of the Bush era and into the Obama era and we are seeing the same kinds of disastrous effects that we came to expect in the Bush Era, it does matter who the ruling party is and it does matter that our president is Obama and not Bush. But sometimes the political playing field is so stuck that the same things will happen anyway. When it comes to conventional politics, switching the Democrats for the Republicans still leaves the same economic structures in place, and means that the same people have to be paid off, the same investments are made in the financial sector, the same cuts are made in the welfare sector and so on. If anyone thought electing Obama was going to be a silver bullet they have realized now that is not the case. In relationship to some of these other areas where you are saying we have been really pushed back, for example the Rush Limbaugh incident around contraception, the Trayvon Martin murder in Florida, it is amazing how insistently history repeats itself. But of course history is going to repeat itself where race relations have not been resolved and where the kinds of attitudes towards sex, reproduction and in particular female sexuality have never been revised. We still live in a culture that doesn’t offer sex education to young women; we still characterize sex education that does occur with sex negativity. We still think it’s important for people to be “race blind” or “color blind.” This week I was teaching Patricia Williams’’ book, The Alchemy of Race and Rights, which was written in 1991 and refers back to the Howard Beach incidents in New York, where three young men were chased, beaten, and one of them died in a clash with white youths in a neighborhood that was conventionally white. She uses this confrontation between black and white youth to ask if is it possible for there to be justice in this country. Here we are some 20 years later and we have the same configuration in the Travyon Martin case. What this tells us is that we have not moved to resolve race relations. There have been no reparations, the banning of affirmative action has been disastrous, and the fiction of color blindness is disastrous for people of color. What can queer temporality tell us? Not a lot, other than don’t trust the narrative of progress. MW: When I have seen you talk recently you have been mapping strategies for resistance through anarchic performance or your idea of Gaga feminism. As someone invested in queer theory, art and performance, I am struggling with how to bring those ideas together with that of a more dominant narrative. That tension is the undercurrent of my question. JH: That might be a question, but that’s not part of the question of how we understand the fact that we are in moment where reproductive rights are being pushed back and young black men are being killed while their killers go free. That was the specific question. That is not going to be answered through an anarcha politics. There might be another question that asks about what kind of impact we can have on the world through different kinds of political practices. That’s a different question. All of these things have to happen on the same time. On the one hand we have to look at current events and see the marks of a long standing history of marginalization and oppression that doesn’t go away just because one wishes it would, and second, one has to see that we have to perform our opposition in ways that are surprising, different and new to capture the attention of a new generation of people for which Travyon Martin and reproductive rights issues are brand new. They don’t necessarily understand them in relation to things that happened 25 years ago. The culture doesn’t hold on to that memory for very long. I am always interested in the possibility of finding new forms of expressing our dreams of our alternative society. To stay stuck in our old ways of expressing opposition is to not take advantages of new circumstances. New circumstances demand new responses. MW: I wanted to ask about the idea of play in your work. What strategies do you think we can adopt for reclaiming that idea both inside and outside of the academy? JH: That’s a great question. I did a forum last week at NYU with Lisa Duggan, Jose Muñoz, Ann Pellegrini and Gayatri Gopinath, that came about because we were talking about my new book. Lisa Duggan made the point that when queer theorists propose social and political projects, they are accused of being ludic. The meaning of ludic is playful. She asked why this has to be a critique, which is what I also hear in your question. I do think there has to be playfulness in the ways we articulate our opposition. To be deadly serious is sometimes to loose people, to loose some of the anarchic energy that is always available when people protest, create surprising collectives, and take to the streets. A lot of protest theater is playful. The ways people have been taking on the Occupy movement have been playful too. I think these are important ways of getting around the total lack of humor in mainstream politics. MW: How do you see feminism and queer politics being enacted and represented in the Occupy movement? Which boundaries do you think are being reified, and which ones are beginning to really come down? How can we think of identity politics in the discussion of the 99%? JH: The mistake starts in the kind of question, “where can we find queer and transgender people in the Occupy Movement?” There isn’t the Occupy Movement and then queer and transgender people in it. The Occupation is queer and transgender people. In fact many of the organizers are/were and will be queer and transgender. I really resist that kind of question because it assumes that there is a normative core to any given movement, then that normative core has to make room for and recognize the queer and transgender people among them. That’s an old fashioned and inaccurate way of thinking about it. MW: What are the boundaries and borders you currently see limiting the potential of feminist and queer communities? Does Gaga feminism tell us something about this? What is the role of masculinity in Gaga feminism? JH: What I am calling Gaga feminism is a form of politics that emerges from what feminist and queer attempts to rethink and reinhabit supposedly conventional sites like the family. It’s a way of taking advantage of the looseness of association that family names nowadays and all of the different disruptions that have occurred that made family into a much more multiple set of relations. Gaga feminism has all kinds of things to say about masculinity. One of the major premises of the book is that you can’t consider shifts and changes in one realm — say, for example, in queer community — without acknowledging that those shifts and changes create a ripple effect in other communities. If there is a surge of visibility for transgender men and those transgender men take as their partners bio-women, what is the meaning of heterosexuality for women? Those women are also changed by the emergence of transgenderism. Second, there are no changes to femininity that don’t come from and situate themselves in relation to masculinity. To the extent that there are women that claim masculinity, transgender men that claim masculinity and the extent to which white masculinity is no longer central, normative or idealized, there are multiple forms of masculinity out there and our job is to recognize them and say there isn’t a normative masculinity that people should be laying claim to anymore. That’s also a project within Gaga feminism. Gaga feminism is a new kind of feminism. It’s not about women, by women or for women; it’s about gender, it’s about sex, and it’s about the end of normal. MW: For a final question, I want to ask you a bit about our project and how we can push the idea of community engagement, community as material to play with. We are trying to create a dialog between new emerging voices and established ones, and I wanted to open that for discussion. What do you think the virtual can enable in this? JH: We don’t know much yet about how virtual community works. There has been much made of Facebook and Twitter and so on in some of the spontaneous revolts and riots that have occurred within urban areas in Europe and in the Middle East. People really overstate that. In many places people are not tweeting the revolution, people are finding each other in the ways they always have. I do think a generation is coming of age in relationship to social networking. That’s not my generation and in a way it’s not your generation. It’s a generation of the five-year-olds now who will be Facebook friends with 1,000 people by the time they are twelve. They will understand virtual relationships very differently than people who keep comparing the virtual to the real. To the extent that some of us have moved through different paradigms of networking, from pre-email exchange, to email exchange, to tweeting and Facebooking, we don’t know and probably shouldn’t predict what that will mean in the future. It is clear that people coming out nowadays have way more access to finding other people like them. When I was a young person, being gay meant being isolated by virtue of the fact it was a minority formation. People grow up in straight families and it was very hard to meet people if you didn’t grow up in an urban area. When I lived in Illinois, when I lived in Minneapolis, people would drive two, three hours to get to the gay bar. If you live three hours from a gay bar now you can use a phone app that will tell you where a gay person is in the restaurant you are in. We don’t know yet what kinds of community those forms will produce or what impact they will have on so-called “social isolation” — that remains to be seen. MW: Thanks Jack. JH: You are so welcome. |