#ReclaimPride: the Editor’s Interview with David Frantz and Martabel Wasserman

|

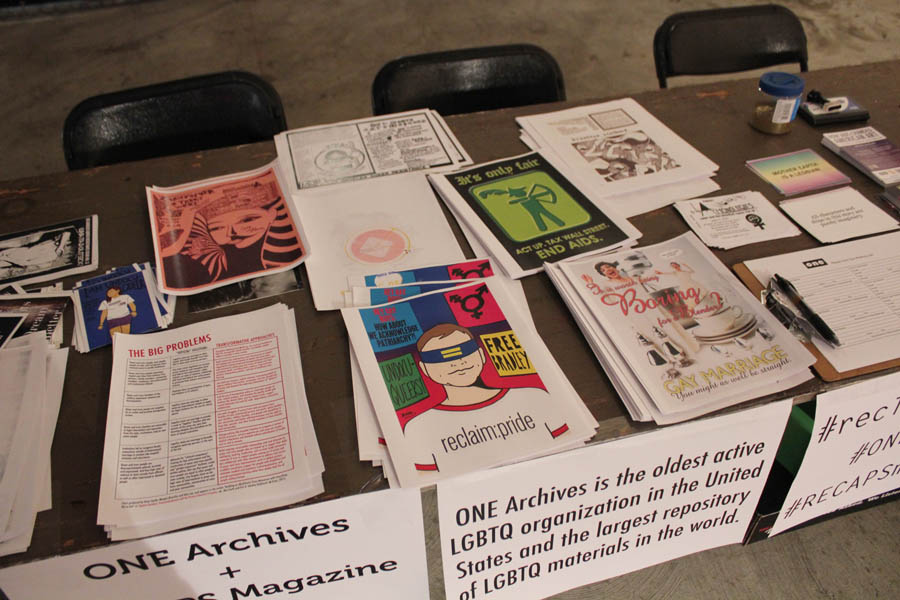

Christopher Street West (CSW), the organizers of the Los Angeles Pride parade, invited ONE Archives to participate in their annual festival as part of a special “Arts and Heritage” exhibition space titled Momentum located in a parking garage under a thumping festival stage. ONE’s curator David Frantz hesitantly accepted the offer to participate in the corporate sponsored, ticketed festival and asked RECAPS to come along for the ride. To “reclaim pride” we dug deep into the archives, crowd sourced, and conversed, in hopes of bridging the event’s radical origins with possibilities for queering the present state of LBGTQ politics. We solicited submissions for button designs, posters, artwork, ephemera, and ideas for guerilla performances to present in our booth and now as this virtual archive, the first annual reclaim:pride issue. 500 buttons, three days underground, and one masked intervention later, we sat down to discuss why/how/and what it meant for us to participate in the festivities of Pride 2013. Martabel Wasserman: Lets talk about how this started. David Frantz: While ONE had a presence at Pride throughout the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, the archive hasn’t participated in LA’s pride festivities in this millennium. Since 2008 ONE has operated a small gallery space (with the very lengthy and weighty title the “ONE Archives Gallery & Museum”) that is located in immediate proximity to all the hoopla that happens in WeHo during Pride. The gallery’s main window literally looks directs out at one of the festival entrances. How to engage the archive in the events of Pride, in both a physical and political sense, has been something I was thinking about as both as a problem and, perhaps, an opportunity. What are we to do this huge throng of people that aren’t necessarily looking for the quite hush of a gallery? How can a queer cultural organization engagement meaningfully with both the event and audience at Pride? This year CSW asked us to participate in a new exhibition within the festival, Momentum, as one of the “heritage” booths. Other invited queer-heritage orgs included the June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives, Impact Stories, The Lavender Effect, and the Center for Political Graphics. The request for participation was vague and last minute: could ONE show something archival? A little injection of history? I felt the assumption was ONE could deliver a very direct gay and lesbian history without much fuss: from the closet, to the streets, to Ellen, to marriage! I’m being simplistic, but the idea of providing clean, easy “history,” something that could be consumed after a few (to many?) drinks was my sense of what was expected. And I personally wasn’t comfortable with that. This wouldn’t be accurate nor would it do justice to the materials in the archive or the monumental work of the people who created it. The idea of producing a historical narrative that’s contained and, essentially, safe is something I think ONE has stakes or even a responsibility, as an organization with its own radical legacy, to counter. The people who made ONE what it is today were also the individuals who marched at the first Los Angeles Pride, and raised hell decades before that. I knew that I wanted to do something that challenged the corporate and consumer model of what Pride has become while also considering new ways in which to deploy the archive. So then I reached out to you to think about possibilities of intervening within Pride. MW: A Pride issue makes so much sense for RECAPS. I realize now that the issues are forming around holidays or annual events where people come together, in public space, like May Day, or affective space, like Valentine’s Day. I both look forward to and dread Pride each year. When you reached out to me it was an opportunity to articulate why Pride makes me sad/anxious/angry and why I still hold onto some hope that it might be something else. It was a chance to engage other people in that conversation instead of getting lost in my own head and heart. DF: The Gay is Angry calendar from 1971 we included is an interesting example of writing history in a cyclical way. The people who made the calendar were writing and memorializing their own unwritten histories. Marches were listed on the dates that they happened only a few years prior. It was a way of keeping the early history of Gay Liberation in focus as it moved forward. It’s such an amazing archival object because it registers all the optimism and anger in imagining a transformative gay politics. For reclaim:pride, the question for us became is it possible to do something radical in the context of Pride today? Did our project have value for people at the festival? Did it encourage forms of reflection and conversation that would not have necessarily occurred? Or did it just annoy people that we were not jumping on the happy-gay bandwagon? MW: At Long Beach Pride last year there was a Boeing “drone float”—which they did not have this year as drone technology has become increasingly contested—and a Wal-Mart Mack truck with a teeny-tiny rainbow flag on it. But then there were walking floats about immigration, unions marching, and lots of proud kinky queers. This juxtaposition highlights the tension inherent in this somewhat democratic use of public space—and the difficulty of negotiating the idea of democracy in gay and queer politics more generally. DF: Right, but we weren’t actually part of the public space of the parade. MW: We were in the ticketed festival. DF: While we weren’t paying for our exhibition space, everyone else in the fair—corporations and other non-profits—were paying a lot of money to have this captive audience of intoxicated people. MW: Who want a lot of free plastic shit. DF: Beads! Covered in logos. MW: Part of reclaim:pride was about appropriating that space and the resources CSW provided for us. Our own giveaways were a mini effort at redistribution. We perceived our buttons as having more value than plastic pride beads or HRC stickers, but that is also just our sensibility. DF: We were distributing something that was questioning the corporate model of plastic advertising. I think also the way we made the buttons was about redistribution. We had an open call for slogans and designs (“Proud of Bradley Manning”; “Fuck the Cis-tem”). We also reproduced buttons from the archive, which was a way of connecting past struggles and ideals to the present (“Anita Bryant Sucks Oranges”; “Women Against Nukes”; “Gay Proud and Angry”). MW: The historical slogans queer the narrative of progress. DF: They question the narrative in a way that is legible on people’s clothing while they are running around the festival. So that questioning actually inserts itself immediately. MW: I think it is noteworthy that there are so many buttons in the archive. They are these tiny things that make big questions legible on your person. They create space for identification, conversation, and for conflict. DF: It’s an egalitarian political gesture. You can put your politics out there and arrange your beliefs in certain ways based on the buttons that you choose. Certainly there is a lot of archival imagery that attests to that. 1975 photograph Courtesy of ONE Archives at the USC Libraries MW: We talked a little bit about Christopher Street West and the festival; lets talk about it in relation to the east coast Christopher Street and what was happening at the Stonewall Inn yesterday [June 26, 2013 when Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court]. On the one hand, it was uplifting to see people so elated. At the same time, the ubiquity of HRC paraphernalia feels like a co-opting of history that location represents. DF: One of the most egregious examples of this co-option is that Harvey Milk’s camera store in San Francisco is now an HRC gift shop. It really speaks to the consumer bend the push for marriage has taken in a lot of contexts. Just the title alone of the space speaks volumes: “The HRC Action Center & Store(!).” [emphasis my own] MW: Speaking of the HRC, and we are so adamant about challenging it, lets talk about the “Danger: HRC is Toxic to Equality” jumpsuit from an Occupy protest that ended up in our display.MW: Speaking of the HRC, and we are so adamant about challenging it, lets talk about the “Danger: HRC is Toxic to Equality” jumpsuit from an Occupy protest that ended up in our display. DF: This came from a very recent donation from the Queer Caucus of Occupy Los Angeles, which included two jumpsuits used in protest against HRC’s decision to honor the Goldman Sachs. There were people who saw it at the fair and recognized it from being at the protest. It’s important that these recent histories of queer resistance are becoming part of an archive and that ONE specifically includes numerous queer voices, not just the predominately affluent, capitalist, white, cis-male voices that dominate the media like HRC; though many under-recognized queer voices – queers of color, gender non-conforming individuals, lower income queers – have historically and continue to not make their way into the archives as much as they should. One of the ideas around reclaim:pride was to provide a space for reflection on past histories alongside recent forms or queer resistance, so the jumpsuit felt like a perfect object to convey these ideas. MW: Occupy was very self-aware about its archival presence for the beginning. As soon as people took over Zuccotti Park, books were being pitched about. It was always already history. DF: Right. Do you think this made it less about transformative change in the present? MW: In some ways it was more like a rupture than an on-going effort. Part of the impulse to document and write the history is also about inserting the role of the individual in the story. But because of policing of public space, and the police brutality against Occupy—which connects us back to Stonewall and the policing of queer people far prior to that—the constant historizing was necessary to make the take over of public space visible DF: You also touched upon on issues of collectivity, which is what Occupy was supposed to be about, and how that was co-opted in ways. That really speaks to Zach’s project as well. MW: Zach is touching on something that is happening in protest culture transnationally, which is the erasure of the individual through a collective identity. Masks and props offer some sort of protection to the individual and allow for that wonderful feeling of being part of something collective. DF: But it’s not just about protection as an individual, its antagonistic against being viewed that way. There is more power in collectivity and anonymity. The Guerilla Girls are an old school example of that. The idea has historical precedent. That something transformative can come from adamantly resisting visibility, which really pushes back against all mainstream narratives of gay and lesbian progress. MW: Good point: the emphasis protection reinscirbes ideas of the individual. DF: We have talked a lot about our reasons for initiating the project and what we desired it to enact, but maybe we should go right to the big question “Did it do what we wanted it to?”; “What were people’s reactions?” MW: It is always so hard to gauge that. Its presence as an archive, and the repetition through representation, is helpful for soliciting more responses to engage with. DF: There were some people that were aware that this was very different from what is excepted at Pride. I saw this from numerous young people as well as a much older generation—who typically have stronger connections to ONE. They were very aware that this was not a new thing, but something they had not found at Pride in a while. These types of discussions—perhaps not the specific issues but the context to engage—did happen at Pride once. MW: Discussions about liberatory politics more broadly are not really part of the Pride that millennials have grown up with. DF: The discourses around marriage, DOMA, DADT, It Gets Better, they have such a choke hold on media representation and information. MW: Those campaigns have value certainly but being left of left means that you have to push at them. Radical queer histories have made those sorts of representations possible, being on the outside you have to keep pushing at the center. DF: It’s not sacrilegious to question mainstream gay and lesbian politics. That is something I feel our community is really hesitant about, or at least something that came up around this project for me. MW: That’s because we are deeply insecure. It speaks to gay shame. DF: Yes it speaks to numerous histories of trauma and shame. MW: Which is why our installation next year is going to be a crying booth. DF: It also speaks to general anxieties about being dissident in American culture. MW: Right, why would you want to be dissident when you know it’s all going to be in the metadata? I think the NSA leak was a collective psychic trauma for our country, even though it is not surprising— it still generates new fears around dissenting. It really makes you think about what you are willing to risk. Bradley Manning risked it all and his sentencing is a way to scare the rest of us. DF: The stakes are high. We are continually told… MW: That it gets better. DF: That corporations have our best interest at heart. MW: And that the government now has the best interest of gay people at heart. DF: In many ways corporate sponsored spaces are the only public spaces we have left. Maybe that calls into question the very nature of dissent in public forum—we have to do things in these spaces and find ways around their limitations, which is really a much larger conversation. MW: Right, the public sphere is not really public. I think when CSW approached you, it was important to say yes despite whatever hesitations you had. We used the space to speak about queer topics we don’t experience directly, from often-ignored trans issues to queer perspectives of the prison system. That kind of representation is what makes curating or editing such a precarious endeavor. How do you use your position within an institution to highlight what falls outside of it, while keeping privilege in the discussion? It is a necessarily uncomfortable line to walk. DF: I think that’s a walk that ONE needs to do more and more. In many ways if “reclaim:pride” was not deployed through the context of ONE, which carries with it the weight of being the largest gay and lesbian archive in the world, I doubt this project would have ever been possible. Using our own privilege as curators, artists, and organizers with degrees and institutional support allowed for this. MW: As gay people, not queer people but gay people, who are part of a moment where we have increased visibility and cultural power, we need to be constantly looking at our own positions of privilege. That is why work on pinkwashing is so important, and why it is in an issue we keep highlighting in RECAPS. The voter rights acts got invalidated and the case against affirmative action was sent back to lower courts right as DOMA was overturned. We have to be aware of that. We can’t just get… DF: Married. David Frantz and Martabel Wasserman, June 27, 2013

|